Iceland’s Constitutional Revision and the “New Constitution”

The promise of political renewal that followed the country’s currency and economy collapsing has stalled in political quagmire.

Summary: In the soul-searching that followed the 2008 financial crisis, which hit Iceland particularly badly, there was a surge of excitement for a brand new constitution. Efforts to maintain a balance between new and old ideas, and input from experts and ordinary citizens, have repeatedly floundered over the years since then. Successive governments have employed different approaches to the subject of the new constitution, and the early promise of a 'new' Iceland has - as yet - led to no concrete outcome.

The Icelandic constitutional revision is a consequence of the international financial crisis of 2008. Iceland was badly hit by the crisis: Three Icelandic banks, having grown exponentially in a short time, were too exposed to survive the crisis. The Icelandic state, unable to rescue them, took them over one by one as they went bankrupt, and the country’s currency and economy collapsed. In such an atmosphere, voices demanding political renewal dominated the public arena. It seemed inevitable that, once the country had been saved from losing its independence, politics and the system of government had to change fundamentally.

It seemed inevitable that once the country had been saved from losing its independence, politics and the system of government had to change fundamentally.

A new constitution, a new Iceland

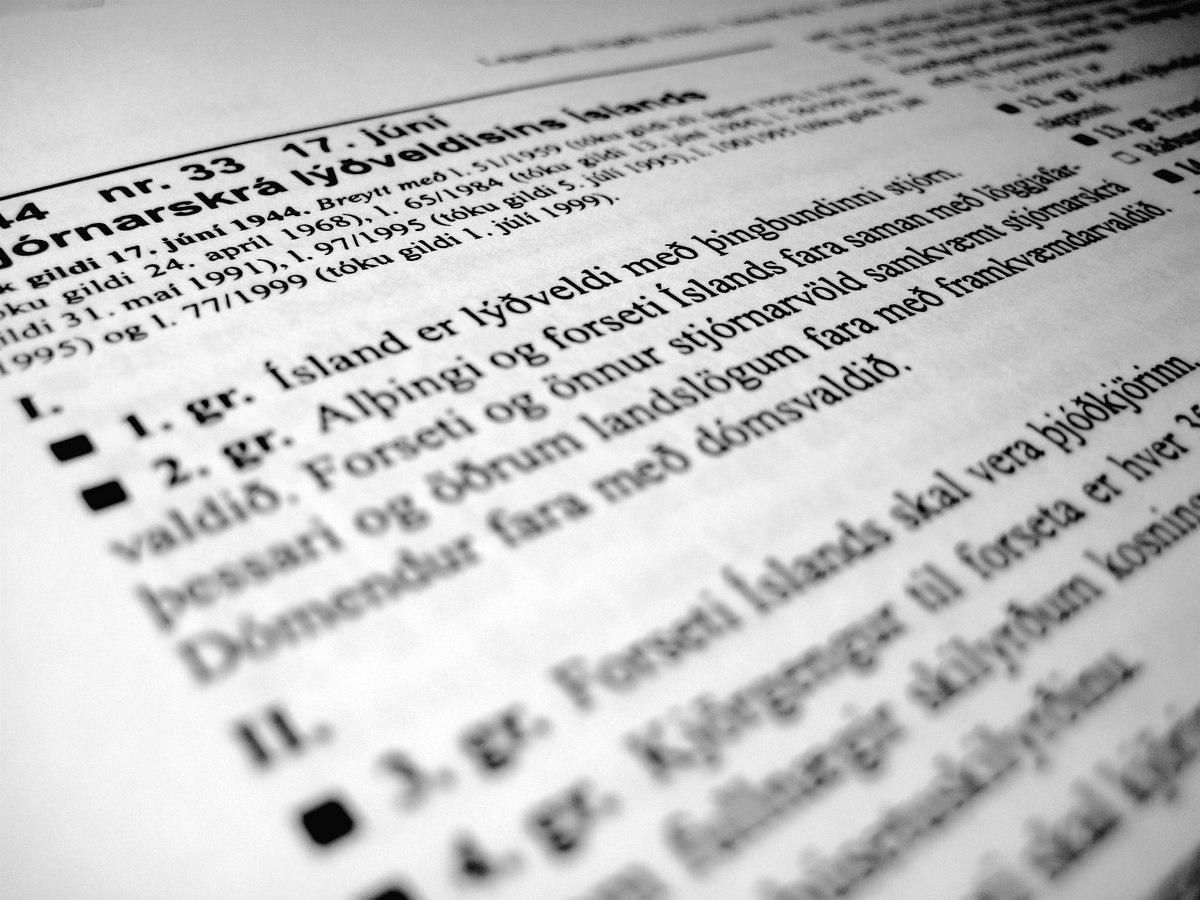

The subject of revising of the constitution had surfaced time and again in the 64 years since Icelanders founded their republic, ending the royal union with Denmark. But this time it was different: Many leading politicians and vocal activists now saw it as a fundamental part of Iceland’s post-crisis transition. At the same time, a new constitution was seen as Iceland’s final step to independence. The 1944 republican constitution had, as previous Icelandic constitutions (including the 1874 constitution on Icelandic domestic affairs and the 1920 constitution of the Kingdom of Iceland), been based on the Danish constitution from 1848.

A national meeting and a Constituent Assembly

After massive protests resulting from Iceland’s economic crisis, the government of the liberal-conservative Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn) and the Social Democratic Alliance (Samfylkingin) collapsed. Instead, the Social Democratic Alliance formed a new government with the socialist Left-Green Movement (Vinstri græn). The new government led by Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, a senior reformist politician, proposed a number of reforms to strengthen democracy in Iceland, including legislation on a Constituent Assembly.

The proposal for an assembly of 25 people was supported by MPs from all parties except the Independence Party. Icelandic citizens over 20 years of age and who did not hold public office were able to run for a seat in the assembly. The conditions for registering as a candidate were to be kept simple, and they would be given the task of revising the Icelandic constitution with a focus on eight topics, including democratic participation, and the management of the environment and natural resources. The result of its work was to be a constitutional bill that would be submitted to parliament for further discussion and approval. The preparations for the assembly included a so-called national meeting where 1000 randomly selected citizens would discuss and articulate their main views and values in order to guide the constitutional revision process.

Election debacle: The Constitutional Council

Elections were held on 27th November 2010 and 25 individuals out of 522, each of whom ran on his or her own platform, were elected to the assembly. After the elections, complaints were made about guaranteeing the privacy of voters and the security of votes. The Icelandic Supreme Court reviewed these complaints and ruled that the elections were invalid. Since no suspicion of fraud was raised, however, the Parliament decided that, rather than call new elections, it would reappoint the 25 elected assembly members to what was now called a Constitutional Council. All except one accepted the appointment to the council, and work was able to start on constitutional revision in April 2011.

An entirely new constitution

One of the first things the Constitutional Council did was to decide not to revise the constitution from 1944, but rather write a new one. As expected, the Constitutional Council also decided to stream its plenary meetings and set up a process for the public to observe and monitor the Council’s progress. Evolving drafts were published once a week on the Council’s website and Council members made themselves available for discussion with individuals and groups. Much of this discussion was conducted online through social media platforms, especially the Council’s Facebook page, which got a large number of visits. Many ideas, proposals, criticisms, and reflections were voiced and discussed there.

The “crowdsourced constitution”

The highly publicized social media exposure of the Council and its direct and uninterrupted communication with the public drew international media attention. But, as international interest grew, and activists and academics also started to observe the process, the emerging bill created by the Constitutional Council began to be referred to as the “crowdsourced constitution”. The drafting of the constitutional bill was a fully transparent process. The Council’s subcommittees were obliged to consider proposals submitted via the official proposal system and debate them. All in all, 323 proposals were received from the public and were discussed in the subcommittees. Around 6000 comments were made on social media. Some of these comments were then discussed further in one or more committee, but no formal process was set up for handling comments or proposals received via social media.

The Constitutional Bill: public support, expert criticism

After four months of drafting and deliberating its Constitutional Bill, the Council unanimously approved a document to be sent to parliament, containing the bill and the Council’s commentary on it. It did not in the end present a radical departure from the 1944 constitution. Rather it reconfirmed the commitment to parliamentary democracy and aimed at introducing and securing a number of new rights, including so-called second and third generation rights, dealing with socio-economic issues on the one hand, environment and nature on the other, in addition to a rich repertoire of civil liberties. It included, for example, rights to a clean and healthy environment as well as “rights of nature” and those of future generations. It also characterized natural resources as “national property”, constitutionally precluding their privatization and stipulating that no one could be given the right to exploit them without full payment.

Although there seemed to be widespread public approval of the Constitutional Council’s work, criticism emerged especially from the academic community. The main concerns were about the composite nature of the bill, which partly reflected the fact that its authors were neither legal scholars, constitutional specialists nor political scientists (although among the members of the Council, there were both lawyers and political scientists). The Council had borrowed from other constitutions (as was to be expected), but the number and diversity of the sources created concerns about the legal coherence of the final document.

The 2012 referendum

In 2012 the Parliament decided to call a national referendum on the constitution, not asking for direct approval or disapproval of the Constitutional Council’s bill, but rather exploring whether voters were prepared to accept it as a basis for a new constitution. This question was grounded in the role parliament must play in constitutional revision. Voters were also asked to answer five more general questions about constitutional issues. There was no explanation provided on what that meant precisely, but the formulation at least suggested that parliament would change the constitutional bill rather than abandon it, given the requisite approval.

The referendum confirmed that the Constitutional Council’s bill enjoyed wide approval among the Icelandic public – with slightly more than 50% participation, more than two thirds of those who voted supported the proposal that a new constitution should be based on the bill.

Parliament wavers and the bill stalls

As fresh elections drew closer in 2013, parliamentary opposition to the bill seemed to grow. Some MPs previously supportive of the bill were now becoming skeptical, partly because of expert criticism. Although rumor had it that powerful interest groups were also lobbying against the bill, there was no open and focused discussion on the individual articles of the constitution to make that opposition clearly visible. In February a compromise was reached according to which further handling of the bill would be brought to an end, keeping the possibility open for its reintroduction at a later point in time.

A center-right coalition was formed after the elections. The new government felt in no way obligated to continue the former process. According to the coalition agreement, a revision process was to be continued under the leadership of the Icelandic parliament. A parliamentary committee was established headed by a retired law professor from the University of Iceland.

Deaths and revival of the “new constitution”

Although a small group of activists continued to fight for a return to the Constitutional Council’s bill, there was little enthusiasm for it over the years that immediately followed. This changed abruptly in the spring of 2016 when the Prime Minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, resigned because of a corruption scandal. In the upheaval that followed, the idea of constitutional renewal – rather than less radical revision – seemed reinvigorated. This had a negative effect on the three amendment bills that were by that time ready for approval after three years of work by a specially appointed committee; the interim Prime Minister’s attempt to push them through parliament failed.

After two parliamentary elections, in 2016 and again in 2017, during which the constitution wasn’t discussed much, a new Prime Minister in 2017, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, announced a fresh revision process in which the constitution would be revised over a period of seven years.

Public engagement and constitutional activism

A central part of the new revision attempt was to encourage and organize public engagement in the process. The method chosen for public consultation this time was a Deliberative Poll in cooperation with the University of Iceland and the Center for Deliberative Democracy at Stanford University. With this method, which involves citizens indirectly in the constitution-making process, it was shown that, although the general support of the Constitutional Council’s bill remained, on some issues the public had views that differed.

The new revision process revived not only constitutional debates among the political parties and in parliament, but also led to a new campaign by an activist group, The Constitutional Society (Stjórnarskrárfélagið), which had continued to argue for a return to the Constitutional Council’s bill and had repeatedly lobbied the political parties to bring the former process to completion. This group argued that Parliament was under a political and moral obligation to act in accordance with the 2012 referendum on the constitution. In 2022, when ten years had passed since the referendum on the constitution, the question “Where is the constitution?” could be seen sprayed on walls and walkways all over Reykjavík.

An unfinished business

While in 2024 the Icelandic constitutional saga is not over, it is indicative of the political environment in Iceland that, despite a widely shared view among both the public and politicians that constitutional revision is long overdue, it has not been possible to create broad political support for any concrete revision. The Prime Minister’s revision process, although not formally abandoned, does not seem to raise much hope: Further constitutional amendment bills are currently being prepared based on the opinion of four distinguished legal scholars, and public consultation – which remains unspecified – is still seen as an important part of the process.

In the 15 years since the financial crisis, Iceland has gone through considerable social and political change. However, the most publicized effort to transform the country, the one that was supposed deliver the foundations of a “new Iceland”, has led nowhere.

Studying the development of constitutions can shed light on how citizens interact with political processes.

This article is published in response to readers' interest in cultural history and open government.

Further reading:

- Ágúst Þór Árnason and Catherine Dupré (eds.), Icelandic Constitutional Reform: People, Processes, Politics (New York: Routledge, 2020).

- Alexander Hudson, The Veil of Participation: Citizens and Political Parties in Constitution-Making Processes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

- Hélène Landemore, Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-First Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).