Islam in Denmark – an historical overview

Despite the public debate since 1980s presenting Islam in Denmark as a new phenomenon, it has for centuries played a central role as ‘the other’ when Danes have sought to explain their collective identity. It is true that many Danish Muslims arrived as a ‘guest workers’ in the boom years of the 1960s and stayed on. They were followed by their families and later refugees, although guest workers and refugees have by no means all been Muslim. Going further back, Islam and Muslims have been a part of Danish history for more than a millennium. Historically, the relationship between majority and minority populations and varying beliefs and social norms has always encompassed both opportunities and challenges. This remains the case today, and while elements of Danish society welcome the dynamics of the relationship, public debate frequently problematises it.

Embedded challenges, 1980s onwards

Denmark has since the 1980s been engaged in a heated public debate with strong populist undertones concerning what is perceived to be the ‘Muslim’ and ‘Danish’ groups within the population. This debate has heavily influenced the agenda during all national and local elections ever since. The debate is needed and inevitable; there are inherent challenges and opportunities in the dynamics between the meeting of beliefs and social norms of a majority and a minority. On the one hand, these dynamics are often problematised in public debates, which are often preoccupied with Danishness and what it constitutes. On the other hand, some segments of the population welcome the opportunity. They meet the challenge to values and social practices rooted in the liberal European tradition – for the benefit of all – and acknowledge that there will likely be a change to local norms. Certain groups seek to build bridges to make it possible to develop new collective habits and traditions where the ever-changing social world will be able to promote inclusion and mutual recognition.

Twentieth century

The presence of Muslims in contemporary European countries that have been traditionally considered relatively peripheral to European colonialism (countries like Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and (West) Germany) has been explained with reference to the increased demand for workers during the industrial boom in late 1960s. The demand could not be met in spite of an increase of women in the labour market, so it resulted in workers from for example North Africa, Turkey and Pakistan migrating to Denmark. The first migrant workers realised the need for further hands and a chain migration was established.

Due to an international economic crisis throughout the 1970s, the Danish parliament in November 1973 stopped labour migration. At the same time, it passed new laws making it possible for migrant workers with a permanent work permit to bring their families to Denmark if they had an apartment fulfilling legal demands regarding sanitation and space. The ensuing family reunification in sociological terms created the budding of norms and social rules that came from, for example, Turkey, Pakistan and Morocco as the families came to Denmark. The migrant workers were all men and their interaction with the host society was limited, but family reunification gave way to increased interactions and this paved the way for the continuing debate about how to integrate and who to integrate.

From the early 1980s, refugees arrived from different areas including parts of the Muslim world hit by civil wars or inter-state conflicts. The refugees frequently came from the following countries, although of course not all of these were Muslim:

- Iran, largely as a result of the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979;

- Lebanon, particularly as a result of the civil war of the 1980s;

- Kurds from Turkey and Iraq due to being severely persecuted;

- from war-torn Iraq, particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s;

- from parts of the former Yugoslavia which encountered division and war from 1990s;

- from Somalia as a consequence of civil war during the 1990s and ongoing violence;

- from Afghanistan due to repeated internal conflicts and international interventions; and,

- from 2011, from Syria due to the civil war.

The steady increase in the number of Muslims raised challenges for the reunified families, refugees and the Danish host society alike. Islamic migrants and refugees, like other minority groups, had to adapt to a different life as minorities in a more-or-less secular country. This often involved a consideration of whether a person’s interpretation of Islam could be reflected in their new environs.

In all Muslim groups it is possible to discern how the parents initially tried to shield their children from being too strongly influenced by values rooted in the surrounding majority society as many upheld the belief that they would at some point return back to their country of origin. For the majority, this ‘myth of return’ never transpired and an acceptance of a need to formulate a different definition of how to be a Muslim began to surface. Similarly, Danes often reflect on the meaning of Danishness or Protestantism, or connected concepts when met with other belief systems and cultures.

Conversion in modern times

A few Danes converted to Islam during the interwar period. After World War II the Ahmadiyya movement intensified its missionary efforts in Europe and, during the 1950s and 1960s, a small number of Danes converted to Islam. In line with the movement´s mission strategy, the converts wrote and published small books and pamphlets written in Danish in an effort to introduce Islam to the wider Danish public. In 1967 the movement was able to inaugurate a mosque (the Djahan Mosque) in a Copenhagen suburb at a time when the Muslim migrant workers were very few in number. The Danish convert Abdus Salam Madsen (1928-2007) in the same year published the first complete translation of the Quran in Danish.

The Nusrat Djahan Mosque in Hvidovre. It was built by followers of the Ahmadiyya movement and opened in 1967. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

From the late 1970s conversion to Islam increased as a result of the greater interaction between Muslims and the Danish host society, and as a result of the establishment of local mosques, Quran-schools, private Muslim schools and Muslim cultural organisations in all parts of Denmark where Muslim families had settled. Initially, Muslims of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds established mosques along ethnic lines in an effort to maintain the interpretation of Islam practised in their country of origin. From the early 1990s, however, this defensive approach was challenged by a new generation of Muslims born in the country who spoke Danish and were generally well-educated. Needless to say, some young Muslims did not acquire these skills and were accordingly less successful, but in this regard the same development was surfacing among young ethnic Danish individuals.

Conversion to Christianity also surfaced, not least among the group of refugees arriving from the early 1980s from different areas in the Muslim world hit by civil wars or inter-state conflicts.

Islam and Denmark over the centuries

It is often overlooked that Islam has for centuries played a central role as ‘the other’ when Danes were in need of explaining their collective identity and that it is not, as often assumed, a new phenomenon.

16th-18th century: shipping led to contact between Danes and Muslims

During the late 16th century and throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries, Islam became more deeply embedded in the collective Danish consciousness than it had done before. The expanding Danish trade by sea with the Muslim world turned out to have unpredicted consequences. An unknown number of Danes were taken prisoner by Muslim pirates (known as corsairs) who used ports along the Barbary Coast in North Africa as points of departure in their endeavour to take prisoners who were to be sold as slaves. In several instances Muslim pirates also attacked areas which were part of the Danish Kingdom. In 1627 Muslim pirates attacked two small islands to the south of Iceland and took several hundred subjects of the king prisoner, brought them back to North Africa and sold them as slaves. Another raid was carried out in 1629 on the Faroe Islands with the same result. This new situation forced the king to act and a special fund was established in 1715 to raise money needed to use to ransom Danes taken captive. The Church was also concerned and sources attest several collections being organised from local churches throughout the country, and a letter dated 5th April 1714 from Bishop Christen Worm strongly encouraged the King to meet his obligations in order to avoid Danish seamen from converting to what was considered the ‘false’ religion of Islam.

Georg Høst served from 1760 to 1767 as Danish consul in Morocco and, in a book published in 1779, he informed his readers that he never during his long stay in North Africa heard of a Dane who had converted to Islam. Other sources, however, indicate that an unknown number did convert and two of them, upon their return to Denmark, published books describing their stay in the Barbary States. One of them, Hark Olufs, lived in captivity from 1724 to 1736 but had a very successful career as an officer in the service of a Tunisian Dey. He even joined his Muslim Master on a pilgrimage to Mecca. He was finally released for his loyal service to his Muslim master and returned back home. The church authorities demanded that he engage in talks with the local Christian priest in order to be re-integrated into the local Christian community. There are also a number of books edited by individuals who were taken captive and spent years as slaves in North Africa and they too indicate that some actually did convert.

| "Hark Oluf's odd adventures or marvellous skirmishes in Turkey, as well as his happy return from there to his fatherland, the island of Amrom in Riber-Stift, based on his own oral account for the sake of remarkable record and published." Picture: The Royal Danish Library (in Danish). |

The reformation and the Ottoman threat:

Islam and Muslims surfaced once again in Danish history as a challenge in the early 16th century during the Reformation. The Reformation constituted an internal European conflict between the ever more powerful Catholic Church on the one side and different kings and princes on the other who were provoked by the Church's interference in politics and the Pope's clever use of bishops and other clerical dignitaries to expand his influence. The European political order was at the same time under pressure from the Ottoman Empire launching a military offensive against central Europe in a concerted effort to expand further. Vienna was put under siege for months in 1529, but without avail. The Ottomans remained a threat until the late 17th century, and in 1683 again laid siege to Vienna, but, once again, the Sultan´s army had to pull back. The threatening political situation is attested in two minor treaties written by Martin Luther, one of the fathers of the Protestant reformation. In the Shorter Catechism from 1529 and in Confessio Augustana from 1530, the emerging Protestant church condemned Islam as a ‘false’ religion, depicting Muhammad as an imposter and an enemy of the true Christian faith cooperating with the Catholic pope in Rome. Luther´s two treaties are still part of the theological foundation of the Danish Evangelical Lutheran church. Despite the mention of Islam in Luther’s catechism and the threat from the Ottoman Empire, Islam is unlikely to have featured greatly in the everyday lives of most Danes.

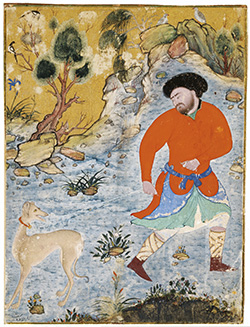

David's Collection in Copenhagen houses an extensive and internationally renowned collection of Islamic art including this miniature from Iran from around 1555 entitled 'Man with saluki dog'. Photo: Davids Samling.

The crusades:

When pope Urban in 1095 concluded an important church meeting in Clermont in France he delivered a speech inviting Christians throughout Europe to take part in a collective effort to reconquer the Holy Land that for centuries had been under Muslim control. In his speech, the head of the Roman Catholic Church informed the audience about new Muslim attacks on Christians. The attacks had forced the Byzantine Emperor to ask the Pope for assistance to curb the new Muslim offensive and, at that point, he considered it the correct time to involve the public. The pope´s request had an impressive impact and only four years later in 1099 an army of Christian crusaders conquered Jerusalem. A number of sources from different monasteries placed throughout Denmark all carefully registered the event in their annals, and during the following century mentioned the participation of a number of Danish crusaders as well as Danish kings taking part in crusades against the Muslims. An analysis of medieval sermons also indicates that many ordinary Danes were familiar with Islam and Muslims as something which threatened the Christian world. Muslims, however, remained a far-away phenomenon and were certainly not something that was a part of the daily life of ordinary Danes.

Despite the public debate since 1980s presenting Islam in Denmark as a new phenomenon, it has for centuries been a part of the wider Danish and European political landscape, even if not a part of everyday life.

Further reading:

- Anne Sofie Roald, Women in Islam: The Western Experience (London & New York: Routledge, 2001).

- Jørgen S. Nielsen, ed., Islam in Denmark: The Challenge of Diversity, Lanham (Lexington Books, 2012.

- Mikkel Rytter, Integration, Tænkepauser 66 (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2019).

- Sherin Khankan, Women are the Future of Islam (London: Rider, 2018).

- Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. The Yearbook is published by Brill in Leyden and up to now 7 volumes are available. Each volume offers well written articles about Muslims in all European countries.

Links:

- Martin Luther and the Reformational Ideas: Enemies and heretics on danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish).

- Interview with the Museum Director of Davids Samling, Copenhagen, on its extensive collection on Islamic art (in English).