An introduction to Nordic arms exports since 1990, with a focus on Finland

All Nordic countries, excluding Iceland, have exported weapons to countries involved in armed conflicts or violating human rights during the post-Cold War period. As Nordic countries often speak for peace and humanitarian work in the international arena, their arms exports have repeatedly drawn criticism. However, Nordic countries have also been highly active in establishing international treaties to restrict arms exports, including their own. In Finland, civil society has been an important player in post-Cold War conventional arms control and has certainly played a role in the state joining the Mine Ban Treaty and the Arms Trade Treaty.

Arms control in the Nordic context

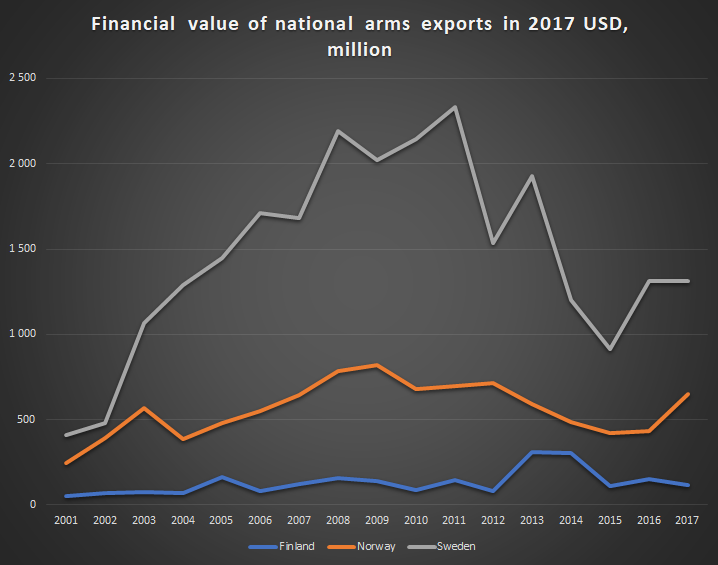

All Nordic countries, except for Iceland, have significant arms industries and have historically benefitted from exporting conventional arms (that is, weapons excluding biological, chemical and nuclear weapons). Since the end of the Cold War, their arms exports have increased despite an increase of arms control. Nordic arms exports are regulated by national laws and international legislation, such as the 2008 EU Council Common Position and the 2013 UN Arms Trade Treaty. States are accordingly not allowed to grant arms export licenses if they might trigger a conflict or be used for internal repression. In practice, the numerous laws and treaties have been interpreted loosely, and Nordic weapons and other military materials are still exported to countries involved in conflicts or violating human rights.

Exporting arms has been a very sensitive and political topic within the four Nordic states which export them, and there has understandably been much public debate over it. It has occasionally led to political scandals, such as the Bofors corruption scandal regarding Sweden’s arms exports to India in the late 1980s and the resignation of the Swedish Defense Minister Sten Tolgfors in 2012. Occasionally, national and international criticism has led to Nordic governments ceasing certain arms exports, as happened in 2018-2019, when Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland stopped export licenses to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates due to their violation of human rights and international humanitarian law during the tragic Yemen War. Civil society, especially peace activists and human rights activists in the Nordic countries, have been central in raising public awareness and encouraging political debate on the exports.

PICTURE: Graph showing the value of national arms exports for Finland, Norway and Sweden from 2001 to 2017. Data source/download further data at Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Arms exports and arms control trends in Finland

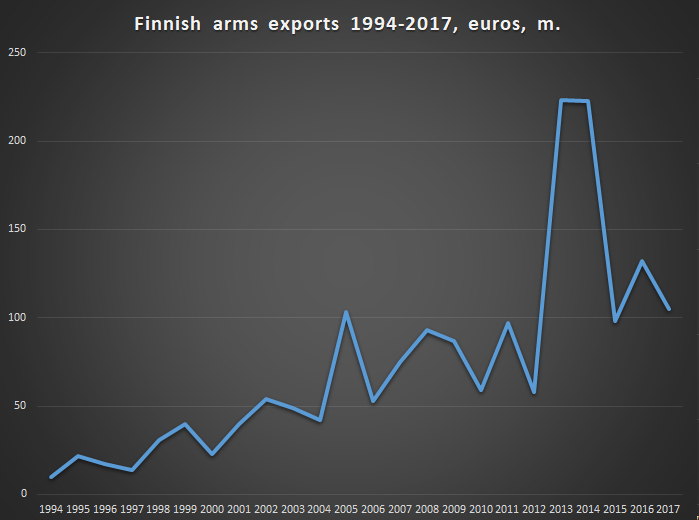

In 1994-2018, the total value of Finnish arms exports was between 10-223 million euros annually, with a general trend of increasing year on year. Since 2000, exports to the Middle East particularly have grown significantly, peaking in 2016 when 63% of annual arms exports was to this area, mainly to the United Arab Emirates. Additionally, Finnish political and public discussion on the arms trade has understandably followed the transnational debate elsewhere involving modern conflicts, as well as peace and human rights issues. This has led to Finnish civil society, such as non-governmental and non-profit actors and organizations, seeking to encourage the state to take an active role in developing international treaties and to comply with them. However, the distinction between civil society organizations and the state can be blurred in a small country. In the early 2000s, both the sitting President and the Foreign Minister had backgrounds in the grass-root peace movement and especially Foreign Minister Erkki Tuomioja, a former peace activist, collaborated closely with civil society during his two terms of office in 2000-2007 and 2011-2015.

PICTURE: Graph showing the value of Finnish arms exports from 1994 to 2017. Data source/download further data at Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Economic depression led to increasing arms exports in the 1990s

In the early 1990s, Finnish arms trade and arms control policies followed the national rules, despite the EU recommendations (which Finland had not yet joined) and those of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) having been acknowledged at that time by the department responsible for export licenses at the time, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs (Ulkoministeriö). On the one hand, Finland complied with arms embargoes and export bans set by the UN and the EU, and supported strengthening international arms control. On the other hand, Finland had not committed itself to any legally binding international treaties regarding the trade of conventional weapons.

PICTURE: The Finnish government was criticized in the 1990s for loosening arms license practices in 1990s, a decision that was influenced by the economic crisis in the country. Photo: Parliament house of Finland (Eduskuntatalo). Photo retrieved from Janne Hellsten on Flickr. CC BY 2.0

The Finnish arms trade was even more criticized after 1994, when the license granting practices were loosened, largely due to major cuts in the defense budget. The cuts were made during the economic depression which saw GDP declining by 14% and the national unemployment rate rising from 3.5% to nearly 20%. The most criticized exports in the 1990s were ones to Turkey and Indonesia, both of which had internal armed conflicts at the time. Civil society, mainly Amnesty International, the Peace Union of Finland and the Committee of 100, the national church of Finland, and many left-wing and green politicians took a stance on the issue. Despite the criticism, the government, consisting of both left-wing and right-wing parties, continued granting licenses to export to both Indonesia and Turkey.

The Mine Ban Treaty: Finland initially refused to sign

In 1992, six human rights and humanitarian NGOs launched the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) demanding an international treaty to ban landmines that kill and injure civilians, a tragedy that occurs often because of insufficient mapping or lack of resources for clearing. The ICBL mobilized public opinion, lobbied governments and communicated with the media, and soon got support from many states, including Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. In Finland, however, committing to banning landmines was considered too risky for national security. Landmines, which Finland already possessed in case of war, were efficient and low-cost for defending the long Finnish-Russian border.

In 1992, six human rights and humanitarian NGOs launched the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) demanding an international treaty to ban landmines that kill and injure civilians, a tragedy that occurs often because of insufficient mapping or lack of resources for clearing. The ICBL mobilized public opinion, lobbied governments and communicated with the media, and soon got support from many states, including Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. In Finland, however, committing to banning landmines was considered too risky for national security. Landmines, which Finland already possessed in case of war, were efficient and low-cost for defending the long Finnish-Russian border.

PICTURE: Transnational civil society has been an important player in post-Cold War conventional arms control. The photo shows a demonstration against the arms trade in London, 9 September 2017. Photo: Alisdare Hickson. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The Finnish Ministry of Defence (Puolustusministeriö) indicated that the landmines in Finland would be mapped and at a later date cleared, minimizing civilian casualties. Therefore, despite supporting the treaty in principle, Finland refused to join it. The parliament was not unanimous, as some left-wing and Christian Democrat (Kristillisdemokraatit) MPs objected and argued that staying out of the treaty would damage Finland’s reputation. The Convention on the prohibition of the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of anti-personnel mines and on their destruction, also called the Ottawa Convention or the Mine Ban Treaty, was signed in 1997 by 122 countries, including all EU states except for Finland.

PICTURE: Finland initially refused to sign the Mine Ban Treaty in 1997 (which was signed by 122 countries, including all EU states except for Finland). It did however at a later date becoming a State Party to it in 2012. Demining in Afghanistan. Photo retrieved from ResoluteSupportMedia on Flickr. CC BY 2.0.

Activists and some politicians did not accept the decision not to sign up to the Mine Ban Treaty and continued campaigning. President Tarja Halonen (Social Democratic Party, Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen puolue), who was elected in 2000, pushed Finland to join the treaty. Halonen was known for supporting global peace work and she was a member of the pacifist NGO Committee of 100 and a former chairwoman of the Finnish Peace Education Institute. In 2004, parliament voted to join the Mine Ban Treaty, and Finland became a State Party to it in 2012, subsequently destroying its stock of anti-personnel landmines. Since then, the Finnish Defense Forces have developed a new form of weapon to secure the Eastern border during a war, having the same deterrence effect as antipersonnel landmines, but functioning in a sufficiently different way as not to break the treaty.

Finland and the Arms Trade Treaty – an attempt to decrease conflicts and human rights violations globally

In the 1990s, a group of transnational humanitarian and human rights NGOs initiated a treaty to restrict arms exports to countries that had poor human rights records or were involved in armed conflicts. In the early 2000s, these NGOs launched the Control Arms Campaign which was aimed at governments and called for a universal arms trade treaty. Finland, which at this point was the only Nordic country involved, became one of the seven initiator states by announcing its support for the campaign in 2003 and began promoting the treaty actively in the international arena. This was largely due to the Foreign Minister Erkki Tuomioja having a strong interest in reducing armed violence globally. Tuomioja was one of the founders and former leaders of the Committee of 100 and had even been sentenced to imprisonment for peace activism in 1969, although the conviction was later overturned by the Supreme Court.

PICTURE: The Foreign Minister of Finland Erkki Tuomioja was instrumental in, amongst other things, Finland being one of the seven initiator states of the Control Arms Campaign in 2000s. Here, he is talking at a colloquium about the future of the Palestine state. Photo: Veera Vehkasalo. CC BY-NC 2.0

Foreign Minister Tuomioja, who has said that the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) was his personal priority during his two terms of office, enabled civil society to collaborate closely with the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, the ministry that was responsible for the treaty process in Finland. After 2006, Finland remained active in the ATT negotiations within the UN by, for example, contacting other countries, supporting the Presidents of the conferences and having continuous dialogue with Finnish civil society. The ATT was approved by the UN in 2013 and came into force in 2014, ratified by 60 states at the time (in January 2020, it has been ratified by 105 states). Finland had actively promoted a maximalist version of the treaty, but the final form was watered down because of objections by powerful arms exporting states such as the US, China, and Russia. This in fact led to the treaty text being ambiguous and it arguably allows states to decide themselves whether granting an individual arms export license would risk the recipient state’s human security or not; it does not bind countries to change their actual practices. However, the ATT was the first UN treaty regulating the international trade of conventional arms and has subsequently given the voices opposing the arms trade a new focus in their campaigns.

Continuing arms exports

Despite the EU Council Common Position and the Arms Trade Treaty, arms exports to areas of conflict and areas of poor human rights have continued in all the Nordic countries, except for Iceland. The contradiction between the states’ efforts to limit the arms trade and at the same time allow an increase in exporting them can best be understood as a matter of national security. The decisions to export weapons to autocracies and areas of conflict have not been taken lightly in Finland but have often been negotiated within the government for several weeks. There has been a genuine will to protect civilians and avoid triggering further conflicts among most Finnish decision-makers. However, the ability to produce modern weapons has, in the end, been seen as necessary for the state’s defense capability and, as there is no use for such weapons during peace time, they are exported to areas that have reason to purchase them. Having a long border with Russia and Finland not being a member of NATO means that the national defense industry often simply outweighs other considerations.

Why, then, would a state that is so heavily reliant on arms exports to secure its own national security; participate in forming a treaty to limit it? While there are many explanations that can be suggested, perhaps the most obvious one is that there was of course variation amongst domestic politicians and policy. Firstly, there was a genuine political wish to reduce armed violence in the world, but it was considered that a 'unilateral protest' (as it was called) would not only be economically disadvantageous to Finland, it would also not necessarily have the desired effect in the recipient countries. This meant that, while some leaders in Finland were willing to restrict their own arms exports, they would only do so on the back of a universal and binding treaty. Secondly, the question of the arms trade has divided opinion among Finnish parties and politicians; while some have wished that Finland would be a pioneer in peace efforts and show an example to the rest of the world, others have prioritized national security and maintaining defense capability. Finally, civil society has had a significant influence by lobbying and pressuring the ministries and governments and mobilizing public opinion by campaigning and communicating with the media.

Further reading:

-

David Cortright, ‘Protest and Politics: How Peace Movements Shape History’, in Mary Kaldor and Iavor Rangelov, The Handbook of Global Security Policy, (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014), pp. 482-504.

-

David Long, ‘The European Union and the Ottawa Process to ban landmines’ Journal of European public policy 9, 3 (2002), pp. 429-446.

-

Jennifer Erickson, Dangerous Trade. Arms Exports, Human Rights, and International Reputation. (New York; Columbia University Press, 2015).

-

Mark Bromley, Neil Cooper and Paul Holtom. ‘The UN Arms Trade Treaty: arms export controls, the human security agenda and the lessons of history’International Affairs 88, 5 (2012), pp. 1029-1048.