The Abortion Law Paradox in the Faroe Islands

Individual stories expose the contradiction between a nation built on equality and a law that continues to restrict citizens' bodily freedom.

Summary: The Faroe Islands has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe and there has been little political will to change it until recently. The lack of abortion rights is contrary to the image the Faroese people have of themselves as gender equal and on a par with their Nordic neighbours. Faroese women have often remained silent on what has been seen as a taboo subject. However, the changing discursive landscape can have a transformative affect on women’s self-understanding and their sense of worth as citizens.

Abortion legislation from 1956 to 2023 in the Faroe Islands

The abortion law of 1956 sets out that a pregnant person may only receive abortion care at a public hospital when they meet at least one of four requirements:

- If the pregnant person’s life or health is in danger (up to the sixteenth week of pregnancy);

- If the pregnancy has occurred due to a violation to the person’s bodily freedom;

- If the foetus’ life or health is in danger; or

- If the pregnant person is deemed unfit to nurture a child.

If the pregnant person is under the age of 18, a legal guardian must approve the abortion too, and if the pregnant person is married, the spouse’s view must also be heard.

The abortion legislation is a Danish law from 1956. Back then, Greenland and the Faroe Islands (autonomous territories of the Danish Kingdom), all had the same abortion legislation as Denmark. In 1959, the Danish state amended their abortion law, removing the fourth reason above. Under the Faroes’ Home Rule Arrangement (Heimastýris(lógin) / Hjemmestyre(loven)), they could choose whether they wanted to adopt amendments to legislation or not. In this case, the Faroe government chose to keep the older version. Denmark once again amended their abortion legislation in 1973 to what is commonly referred to as ‘free abortion’, meaning that it is a pregnant person’s right to opt for an abortion up until the twelfth week of gestation.

On the 8th of January 2023, a proposal for revising the abortion legislation was presented by the Minister of Justice in the Faroe Islands, which would also give women over 18 the freedom to have an abortion up until the twelfth week of gestation. The Faroese Parliament will vote on the bill later in 2024.

2017 saw increased public and media attention on abortion

From July 2018, Family Affairs were to be devolved to the Faroese government in accordance with Home Rule, which allows the Faroese government to choose when to take over particular areas of political affairs. The Faroese government made it clear from the outset that they had no intention of amending the abortion legislation immediately, but what was primarily a practical procedure (with no change to the law expected) became a wider matter of public interest - both in the Faroes and internationally.

Until 2017, abortion had not really been a topic of debate in the Faroes, neither in private or politically. If it was discussed at all, it was usually from the point of view of anti-abortion. The only organisation actively focused on abortion was the anti-abortion organisation, Pro Vita Faroe Islands (Føroyar Pro Vita). When it became clear that the issue of abortion legislation was to be devolved, the Christian and pro-independence political youth party, the Young Centralist Party (Ung Fyri Miðflokkin), took the opportunity to generate a discussion on the Faroese public’s opinion on abortion. To them, this was an opportunity to revise the legislation into the Faroese language and context, as well as to further restrict access.

The debate also activated a group of women who felt a pro-choice voice was missing and they began to meet secretly in a room in the public library in Tórshavn to plan the organisation of a pro-choice voice. These women were convinced that there were people in the Faroes that did not agree with Pro Vita and the general anti-abortion opinion found in the public sphere, but no one knew where to turn to for support. This viewpoint was first presented through a newsletter op-ed in September 2017.

In 2019, an election was held and interest in abortion as a topic grew, although any debate was soon silenced. People were not used to talking openly about abortion, which made any wide-ranging discussion challenging. Some anthropologists have postulated that this is a characteristic of small island societies like the Faroe Islands with its population of only about 54,000. There is a tendency to shy away from potentially antagonistic discussion because people are always somehow related or connected, and they need to be able to face each other repeatedly, in public as well as in private settings.

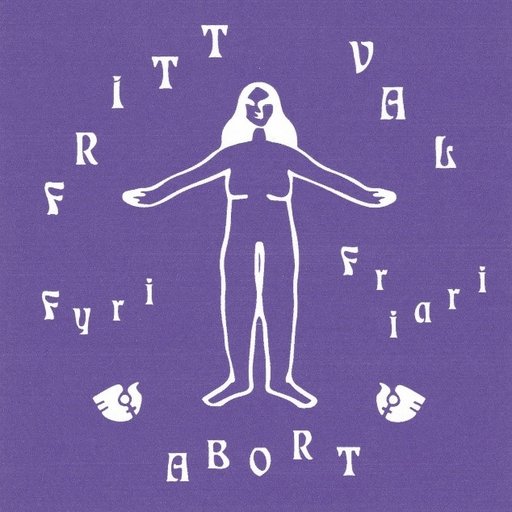

In fact, it was not until the election in September 2022 that the matter of abortion was properly debated. A young political candidate even stood forward and confessed that she herself had had an abortion, and that she was a proponent of abortion rights in the Faroe Islands. In the meantime, the pro-choice organisation, Frítt Val, gathered more wind in their sails, and were highly active and often referred to in the media (as was Pro Vita). Frítt Val and the women who have stood up to tell their stories, as well as abortion finally being discussed more openly, have paved the way for a valuable, alternative discourse on the subject in the Faroe Islands.

Giving a voice to a taboo subject

In my research, I have analysed women’s experiences of reproductive dilemmas based on conversations and participant observation. My findings have illuminated the relationship between motherhood, womanhood and citizenship.

Reproductive stories and stories of experiences with abortion often became untold narratives in women’s lives. The degree to which they kept quiet varied, as did the reasons why. In my research I have described these different ways of being silent as one of many ‘manoeuvrings’. At first glance, this may give the impression of women being supressed. While silence may indeed be a result of suppression, of someone/something else having power, my research shows that the silence may also have a purpose. Against the backdrop of small-scale island society, where 'everyone knows everyone', acts can become identifiers of a person's moral compass, and this motivated many of the women to stay silent about their pregnancy and abortion.

Silence as 'manoeuvring': Silence is not necessarily a reflection of a lack of agency, but it can be a strategic act.

In the Faroe Islands, where having children is an important value, and women are expected to want to have and care for children, an abortion may jeopardize present and future relationships. Thus, keeping silent is not only a way of achieving access to abortion care (as no one must know that you do not truly fulfil one of the four legal requirements for abortion), but it may also be a strategic act to maintain and secure one’s social belonging in Faroese society. So, although this constrained choice may seem anti-feminist and powerless, it is carefully considered and continuously weighed up; since admitting to one’s experiences and the choice one has made (to have an abortion) may not only affect oneself, but reach extended relatives and future generations.

So, although this constrained choice may seem anti-feminist and powerless, it is carefully considered and continuously weighed up.

A paradox in Nordic welfare citizenship

The Nordic societies are often considered as having attained gender equality and secured reproductive and sexual rights. However, this is not always as simple as it looks. In Denmark, for instance, which has had abortion on-demand until the twelfth week of gestation since 1973, issues remain around the different moral stances embedded in the system. There has been recent research on approaches taken towards individuals seeking late-term abortions, permission for which has to go through a special committee, as well as moralising attitudes by health staff. (See Petersen and Rothmar, and Heinsen's articles for more on this).

Studies on welfare societies highlight the relationship between state and citizen as an exchange relationship, where the state expects something in return for basic behaviours on the part of the citizen. Studies show that people in the Faroe Islands have similar expectations. However, my research shows that when women are faced with a restrictive reproductive landscape and ‘break the taboo’ by daring to talk about their need for abortion, they find themselves almost surprised by the lack of typical ‘Nordic’ values. Restrictive abortion legislation is paradoxical: How can a nation be built on values of equality, solidarity and universalism, but at the same time restrict female citizens from enjoying bodily freedom?

Looking to the future: Reimagining a Faroese society for women

Abortion legislation that permits women to opt for abortion until the twelfth week of gestation would relieve women from the disadvantage of being treated with randomness and social injustice. It would also relieve them from the burdensome and costly trip to Denmark, and may also alleviate them from uncertainty about their future and the feeling of being othered. It is hoped that, instead, they would simply feel like citizens on the same terms as others.

The recent turbulence in the moral and political landscape in the Faroe Islands has affected women's experiences of abortion, their feelings of loneliness and 'otherness'. They are not so alone with their choices and experiences, which are now seen as legitimate and important, and I would argue that the changing discursive landscape has had a transformative affect on women’s self-understanding and sense of value as citizens.

The article draws on previous and current research by the author particularly her recent PhD from 2023 and research carried out within the framework of the research project 'Reproductive Manoeuvring: an ethnographic study about women’s abortion and other reproductive experiences'.

Anthropology can illuminate the challenges that individual's face alone.

This article is published in response to readers' interest in gender and the postcolonial relationships continuing in the Nordic countries.

Further reading:

- Annika Frida Petersen and Janne Rothmar Herrmann, 'Abortsamrådenes hemmelige liv : Praksisanalyse af en Black Box forvaltning' [The secret life of abortion councils: practice analysis of a Black Box administration] Ugeskrift for Retsvæsen, Bind 2021, U2021 B.190, (2021) pp. 190-201.

- L.L. Heinsen, C. Bruheim, & S.W. Adrian, 'Orchestrating moral bearability in the clinical management of second-trimester selective abortion'. Social Science and Medicine, 338, Article 116306 (2023).

- L. L. Heinsen, The Moral Labor of making Death: An Ethnography of Second-trimester selective Abortion in Welfare State Denmark. (2023) Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

- Turið Hermannsdóttir, Maneuvering in Silence: Abortion Narratives and Reproductive Life Histories from the Faroe Islands in Medical Anthropology 41,8 (2022) pp. 810-823.

- Turið Nolsøe, 'Biopolitisk deliberation: Den færøske abortbevægelse som retorisk, reproduktivt medborgerskab'. Rhetorica Scandinavica (2023) p. 86.

Links:

- See more research on motherhood and social change via the research project Gendered Island Futures: generational perspectives on motherhood and change in the Faroe Islands, funded by Danmarks Frie Forskningsfond (Danish Research Council).