Pop culture, Vikings and historic Nordic gender equality?

Gender equality is a fundamental part of the Nordic brand, and right-wing political actors as well as extremists use ideas of gender equality in support of anti-immigrant and racist agendas. The pop culture image of Viking women as ‘independent’ and ‘equal to men’ provides one way in which gender equality as an aspect of Nordicness has gained historical legitimacy. New research continues to demonstrate the varied roles that women had in the past and historical media are required to be “authentic” whilst really telling the kinds of stories people want to see.

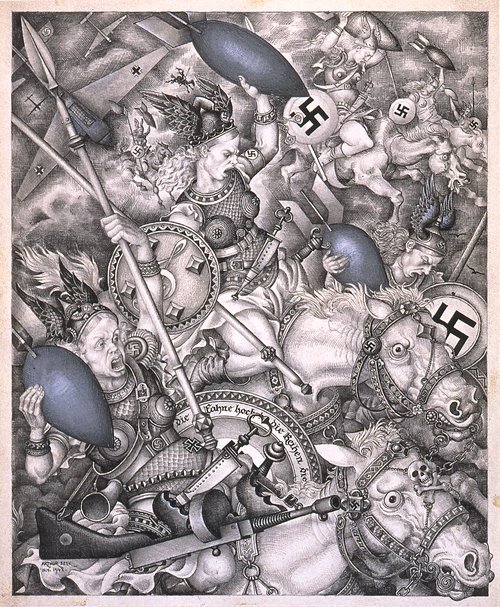

While Vikings may not ostensibly be that important to Nordic people’s self-image, they form a part of their social context, both through branding and how the Nordics are imagined by others. Not all stakeholders in the “Viking” image are Nordic, nor do they all have a strong political agenda; however, essentialist ideas about the Vikings repeated in popular culture can perpetuate particular racial ideas about Nordicness and are often appropriated by certain ideologies. The use of Viking imagery and symbolism by fascist and racist groups has a long history that continues to the present.

The Viking Age (ca. 750–1050 CE) has provided a rich palette of cultural symbolism adopted into Nordic branding. Finding expression in political and consumer advertising targeting both Nordic and external consumers, Vikings provide perhaps the most widely recognised symbolic shorthand for the Nordics. Partly as a result of the historic success of Sweden in marketing the idea of Nordicness abroad, Viking symbolism has gained at least surface-level relevance in all of the Nordic countries – even if it is perceived as somewhat of a caricature. Additionally, Viking imagery has become ubiquitous, communicating traits and ideals associated with the Vikings – and by extension the Nordics – such as strength, adventurousness, wilderness and nature.

Progressive values such as gender equality are a fundamental, ideological part of the Nordic brand, and Nordic countries tend to score highly on international gender equality indexes. In Stockholm or Copenhagen, it is common to see fathers pushing prams, and Finns will tell you that they were the first country in Europe to give women the right to vote in 1906. The reality is, of course, far more complex, and much more work remains to be done for gender equality in all of the Nordic countries. What is important in this context is the significance of gender equality to the Nordic “folk soul” – the idea that gender equality is essential to Nordicness. Therefore, people, cultures or religions perceived to not embody gender equality can be excluded from being Nordic

Recent high-profile research into female Viking warriors, alongside a global rise in interest in Viking-themed media, has brought out romanticised notions of apparently historical Scandinavian gender equality. Portrayals of (conventionally attractive) strong, independent women in Viking-themed marketing and advertising play on creating links between modern Nordic women and their ancient counterparts. Together, these ways of creating, showing, repeating and disseminating seemingly “historical” narratives continually re-establish the idea of gender equality as an essential Nordic characteristic, through its perceived historical basis.

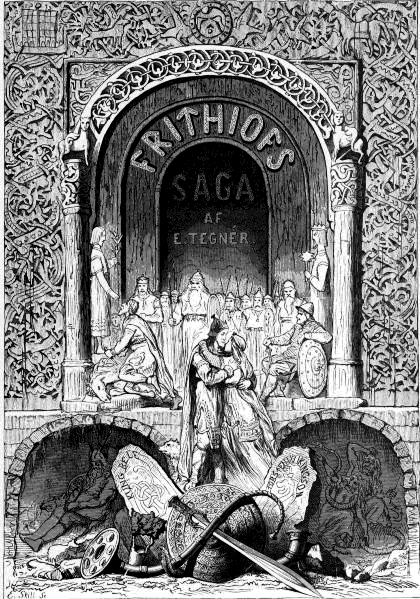

The Vikings of 19th century Romanticism and pop culture

One way in which gender equality has become an essential characteristic of Nordic identities is through its integration into historical narratives. This can be done in a formal way, for example through state education, or in how research is presented to the public through news media, documentaries and museums. It can also be informal, through representations of the past in popular media such as historical fiction, video games, music, movies and television shows. Although formal historical or archaeological research is perhaps more credible, it is not always the most common or accessible way for people to consume ideas about the past.

During the 19th century, the idea of nationhood bloomed across the European continent. National romantic ideas were employed to give nations an emotional core, legitimising them as nation-states through the creation of an historical people, with one language, one culture, and one heritage. Nations themselves were reimagined as female figures, in need of protection from external threats. A revival of interest in folklore and the common people ran alongside the creation of formal national histories. In Scandinavia, these narratives often focused on the Viking Age: a period lacking a written record, allowing it to be more easily used as a setting for a heroic past. The (fictional) image of the horned helmet, for example, originates from this time.

Many of the characteristics that became associated with the Scandinavians imagined by national romanticism already predated the 19th century. Ideas of physical strength, courage, honesty, strongly connected to the physical effects of cold northern climates on the body, were already written about in the middle of the 18th century by Montesquieu in his De l'esprit des lois (‘The Spirit of the Laws’, 1748). As national histories became more clearly codified, these characteristics came to be seen as “essential” to contemporary and historical Nordic people. They would be formative of the Romantic image of the Viking. Similar ideas would continue to be repeated in European race theory and eugenics, further establishing perceived connections between cultural traits and genetics or physiology.

Warrior women and feminist Vikings

The early Romantic images of the Vikings focused on masculinity and are largely what was responsible for the popular image of the heroic, muscular seafaring warrior wearing a helmet with horns. The position of women, though still considered to have been respected, was largely limited to holding power in the domestic setting. Nevertheless, they were conceptualised as more liberated, holding more authority than their Christian contemporaries.

Because the creation of knowledge – including historical knowledge – and social values inform each other, historical and fictional depictions of Viking women, too, reflect the concerns of the society producing them. New research continues to demonstrate the varied roles that women had in the past, enabled by a foundation of feminist academic discourse. Consumers continue to demand historical media that feel “authentic” whilst telling the kinds of stories they want to see.

Viking women as the keepers of the keys, mistresses of the home who ruled in the absence of men, can be rehabilitated to fulfil the need for a retrospective feminism distinct from other contemporary historical societies. However, the idea of Viking warrior women has gained increasing media attention, particularly following the 2017 publication of the re-assessment of grave Bj 581 from Birka, Sweden, that showed that the deceased buried with a full set of warrior gear was genetically female. Female Viking warriors have also featured prominently in pop culture, from Lagertha and her warband in the popular TV show Vikings, to the female Eivor the player can choose to embody in the video games Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla. Besides allowing women to seem empowered through taking on a traditionally masculine role, popular depictions of Viking warrior women also give them sex appeal. It is possible to argue that, by playing into longstanding tropes of comic book-esque warrior women, the fictive or marketing portrayals inspired by Viking Age women become more acceptable to male consumers.

Credible research is used in support of the feeling of “authenticity” experienced by the consumer when engaging with historically inspired media. However, research can be rejected when it deviates too far from what the consumer expects to see based on their existing knowledge and preconceptions. Neither archaeological and historical research, nor fictional portrayals of Viking warrior women, have escaped criticism from the public – or, indeed, researchers!

Personal identities and the Viking brand

Stakeholders interact with heritage in different ways. While for an individual, heritage can provide a sense of belonging, it can also be harnessed in political discourse or used to create in-groups by those wishing to exclude people who do not fit in. Ethnic belonging is flexible and largely self-defined, with different aspects of ethnicity having different meanings from one situation to another. Groups of people created through shared heritage are often actually very heterogeneous. Nevertheless, they are held together by self-identification as a group, and the group’s recognition by others as distinct. How individuals construct the features defining the group can be quite different from what an outsider might consider important.

In a small-scale survey from 2019, we asked anonymous internet users mostly from the Nordic countries how they view Viking women and contemporary Nordic women. The adjective most used to describe both was ‘independent’. Other words commonly used to describe both were ‘respected’ and ‘equal to men’, as well as physical traits such as ‘blonde’ and ‘white’. At the same time, most of the respondents stated that they saw no continuity between Viking women and present-day Nordic women. In contrast, almost two thirds of non-Nordic respondents believed that the image of a Viking woman was important for present-day Nordic identity.

Even though Nordic respondents did not personally believe their image of Viking Age women affected their view of present-day Nordic women, their responses hinted at the “Viking brand” forming part of their social context: the symbolism that Nordic countries and Nordic businesses use to market themselves, and how the rest of the world views them. The undeniable undercurrent was the image of a tall, strong, blonde people, situated in wide landscapes that form the (untouched, natural) setting of their independence and freedom. The same national romantic ideals are effectively timeless and can be translated to almost any time period, but their most recognised and understood deployment has been as part of the creation of the Viking image.

Right-wing “Vikings” and feminism

The idea of the independent Viking or Nordic woman coming through in our survey results fits with other interdisciplinary research in gender studies and ethnic relations, suggesting that gender equality is often framed as inherently Nordic. Its idealisation has allowed far-right groups and political parties to use it to discriminate against others. While the far-right generally do not support the rights of women or minorities in other circumstances, they will defend idealised Nordic gender equality against perceived foreign others.

The political party Sverigedemokraterna (Sweden Democrats) in Sweden or the Soldiers of Odin (SoO), a street patrol group started in Finland in 2015, among others, have stressed the importance of women’s rights. They portray gender equality as incompatible with racialised immigrants, or the religion Islam explicitly. Islam has for a long time been created as Europe’s “Other”, and something that Europe is constantly described in opposition to: if Europeanness, or Nordicness in this case, has “modern gender equality”, then Islam cannot have it – and vice versa. Similar views were expressed by a minority of respondents to our survey, who directly associated skin colour with Nordicness, and positioned Islam or Muslims as incompatible with – or threatening to – Nordic women. In these cases, racist ideas are being disguised as attempts at feminism.

The use of Viking imagery and symbolism by fascist and racist groups has a long history that continues to the present. The Sweden Democrats’ propaganda images, SoO’s name and branding, or the Nordic Resistance Movement’s flag using the Tyr-rune are only some examples. Outside of the Nordic countries, similar examples can be found: from the shields carried by some attendees of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017, to the SoO’s own international chapters. In the wider context, they are part of the fascination the extreme right has for imagined medieval histories. Playing on the idea of protecting the integrity of women perceived as part of the cultural heritage in-group, these groups use romanticised, “essential” qualities associated with their culture as the foundation for excluding others.

In the context of the Nordic countries, Nordic women’s “essential” qualities boil down to independence and self-determination. These qualities have been given an imagined historical lineage to pre-Christian times and are easily placed in opposition to another Abrahamic religion: Islam. At the same time, the association of a particular skin or hair colour with both historical and contemporary Nordic women by some allows these to be seen as ethnic – rather than cultural – traits. This is not to suggest, however, that most people who conceptualise Viking and/or Nordic women as independent and equal to men support extreme right-wing ideas. Rather, that the idea of a distinctly Nordic historical gender equality has become appropriated into the underpinnings of racist and anti-immigrant ideologies in Europe and North America. Many of the proponents of these same ideologies have inherited Viking-themed symbolism from early 20th century fascism.

Global stakeholders in the Viking brand

Despite the appropriation of Viking imagery for diverse goals, Vikings are relevant to a huge variety of stakeholders, within and outside of the Nordic countries. Some, such as the Swedish LARP group Vikingar Mot Rasism (Vikings Against Racism), have reclaimed the image of the Vikings and taken publicly anti-racist positions, campaigning actively against discrimination and social injustice.

The success of Viking-themed pop culture and media has meant that the idea of being a Viking has expanded beyond the Nordics – although some commercial DNA testing companies have marketed personal genetic connections to Scandinavia as being “authentically” Viking. It is worthwhile to note the dangerous underlying connotations of the greater value given to some mythologised genetic backgrounds. Regardless, people all over the world can buy into the visual symbolism of the Vikings. Heavy metal and folk music fans can wear museum replicas of Thor’s hammer pendants, buying into the aesthetic of what Will Cerbone has called the ‘exotic past.’ Some may choose to shave and braid their hair like the heroes of the Vikings TV show. Avid gym-goers and amateur athletes might adorn themselves in Viking-themed clothing whilst training for the Tough Viking obstacle race (held around Scandinavia and Finland every year): They may be seen embodying the physical strength associated with the Viking of essentialism. Likewise, they are buying into the modern “Viking” identity being sold to them by the clothing designers or race organisers and the like. However, not all stakeholders are necessarily endorsing the full semantic – and oftentimes problematic - baggage of its symbolism.

Further reading:

- Anders Neergaard and Diana Mulinari, 'We are Sweden Democrats because we care for others: Exploring racisms in the Swedish extreme right', European Journal of Women’s Studies 21, 1 (2014) pp. 43–56.

- Barbora Žiačková and Saga Rosenström. (forthcoming) 'The North engendered: Mythologized histories, femonationalism, and the Finnish perspective on the imagined Viking-Nordic ideal'. In Hoegaerts, Josephine et al (Eds.) Stories of (de)coloniality, belonging and exchange: Critical perspectives on Finnishness, (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, forthcoming in 2021).

- Carl Olof Cederlund, 'The modern myth of the Viking', Journal of Maritime Archaeology 6,1, (2011) pp. 5–35.

- Will Cerbone, 'Real men of the Viking Age' in Albin, Andrew et al (Eds.) Whose Middle Ages?: Teachable moments for an ill-used past, (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019) pp. 243–25.