Disability policies and movements in the Nordic countries since 1945

During the last century, the situation of people with disabilities in the Nordic welfare states has changed dramatically. For a long time disability was regarded as an issue for the national welfare services, which had a marginalizing effect from a legal point of view, characterized by medical diagnostics, accommodation in mass institutions and exclusion from education and employment. But, following the social and economic transformations after World War II and the ambitious promises of the Nordic welfare model, this absence of rights for disabled people was no longer deemed acceptable. Nordic disability rights activism (consisting of parent associations, self-advocacy organizations, public and political supporters) reached its peak in the 1970s and early 1980s, when protests and awareness campaigns led to a new social and rights-based understanding of disability as well as legal reforms. Today the movement is somewhat fragmented, but maintains an important role in policy-making and monitoring the implementation of disability rights.

Early developments: From charity to state welfare

Over the past century the situation of people with disabilities in the Nordic countries has changed profoundly, not least thanks to the efforts of disability rights movements that emerged since the post-war period.

Disability associations had already existed since the early nineteenth century, but the care of their members was largely the responsibility of families, municipal poor relief and charities. These were complemented with special institutions like the Manilla School for the Deaf-Mute and Blind in Sweden (1817), Denmark’s first institution for mentally and intellectually disabled children Gamle Bakkehuset (1855) and the Christiania Blind Institute in Oslo (1861). Together, these organisations created and perpetuated a system of disability care that segregated people with disabilities from the majority population and distinguished between different needs or disabilities until well into the twentieth century.

This began to change in the 1940s and 1950s, as modern welfare policies were implemented and people with disabilities became part of public social security. However, the traditional system of state-run institutions was maintained and further expanded, creating an ever-widening gap between disabled people and the general population. In addition to their geographical isolation, special institutions for people with physical and sensory disabilities frequently lacked suitable teaching material or room for leisure activities, and training in outdated crafts like basket-weaving offered hardly any work opportunities. People with intellectual disabilities were furthermore subjected to eugenic ideas, often resulting in their lifelong institutionalization and medical interventions such as sterilization – legally practiced until well into the 1970s. This understanding of disability as primarily a medical problem was also evident in the regulation of disability pensions, which were usually tied to medical and care services and did little to stimulate qualified training, regular employment or participation in community life.

PICTURES: A man with a guide dog in Stockholm, 1950s. Photo: Karl-Heinz Hernried, Nordiska Museet (Europeana Collections 1, CC BY-NC-ND 2.5) | Training in basket-weaving for the visually impaired at Huseby kompetansesenter in Oslo, 1953. Photo: Leif Ørnelund, Oslo Museum (Europeana Collections 2, CC BY-SA 3.0).

| Disability terminology: The vocabulary we use to talk about people with disabilities is a sensitive issue that reveals a lot about contemporary perspectives on disability. Terms that we today perceive as highly degrading and stigmatizing were in the 19th and early 20th centuries widely accepted categories to distinguish between different impairments and their respective treatments in medicine and social welfare. In 1980, a new WHO classification differentiated between ‘impairment’ as a physical or mental limitation, ‘disability’ as a functional limitation in regard to a particular activity, and ‘handicap’ as a disadvantage in social life. |

|---|

1950s and 1960s: Challenging institutions and care of persons with intellectual disabilities

Parent associations:

One of the first groups that objected to the often dire conditions in special institutions were parent associations. Advocating on behalf of their intellectually disabled children, their demands included smaller housing units, and more personalized care, leisure and education provision. Even though the influence of parent associations differed across the Nordic countries, over time they succeeded in establishing lasting networks, increased the pressure for political and administrative reforms and brought the issue into public awareness. Examples of parent associations include (current names given here):

- Danish Society for the Welfare of the Intellectually Disabled (Landsforeningen LEV), 1952

- Finnish Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (Kehitysvammaliitto), 1952

- Swedish Association for Children, Youths and Adults with Developmental Disorders (FUB), 1956

- Benefit Society for the Mentally Disabled (ÁS Styrktarfélag) in Iceland, 1958

- In the mid-1960s Norwegian journalist and filmmaker Arne Skouen, father of an autistic daughter, co-founded the advocacy group Justice for the Handicapped (Rettferd for de handicappede) and the Norwegian Association for the Mentally Disabled (Norsk Forbund for Psykisk Utviklingshemmede, NFPU)

The Danish Mental Retardation Act: normal as possible daily routines:

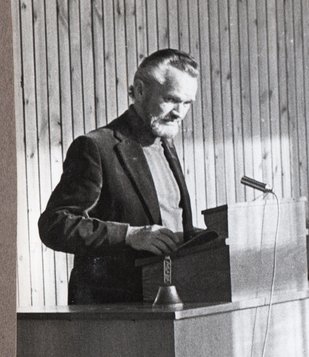

The 1950s and 1960s also saw important legislative changes. A start was made in 1959 when Niels Erik Bank-Mikkelsen from the so-called Danish Service for the Mentally Retarded drafted the Mental Retardation Act, in which he called for the right of people with disabilities to have living conditions and daily routines as ‘normal’ as possible.

Smaller group accommodation, education and vocational training were introduced, as well as leisure activities and psychological counseling services, and in 1967, Sweden and Norway adopted similar laws. It should be noted, however, that these were primarily administrative reforms as a comprehensive decentralization and eventual closure of state institutions did not take place until years later. A curious exception to the ‘normalization’ of disability care in the Nordics was Finland whose 1958 Rehabilitation Act stipulated that accommodation in mass institutions was a central pillar of disability welfare until it was repealed in 1977. This stood in stark contrast to Finland’s earlier pioneering role in removing voting restrictions for persons with intellectual disabilities as early as 1972. In Sweden, such restrictions were abolished in 1989. In the other Nordic countries, discussions about the implementation of full voting rights for persons under legal guardianship are still ongoing.

PICTURE: The "Father of the Normalization Principle", Niels Erik Bank-Mikkelsen doing a speech at a podium. Photo: Henning Jahn.

| Disability terminology in the Nordics: |

|---|

|

Care scandals and the role of investigative media:

Yet another element of change was critical media coverage. In 1959 a radio report by Swedish journalist Lis Asklund about Eugeniahemmet, a Stockholm-based institution for young people with physical disabilities, revealed a strict regime of discipline and punishments even for minor misdeeds. The report sparked a debate about what many Swedes felt was a gross violation of core societal values, and institutions for the disabled as well as the people working there became exposed to a critical public with little tolerance for such conditions. A similar scandal was uncovered by a Norwegian newspaper in 1974. The so-called ‘Gro’-investigation reported coercive measures and abuse in the Central Institution for the Mentally Retarded in Klæbu near Trondheim. After an inquiry commission had confirmed serious irregularities, the Norwegian government introduced legislative rights for the residents of special institutions and improved their control mechanisms.

1960s and 1970s: Disabled activists speak up

In the 1960s and 1970s, disability rights activists – in the Nordics, but also internationally – came together in what can be considered a new social movement. Using disability as a marker for persisting shortcomings in the Nordic welfare societies, people with different disabilities such as visual, hearing or mobility impairment consolidated their demands for reforms under a cross-disability umbrella. Within these discussions, a new understanding of disability emerged as a human rights issue, shaped by social, political and environmental factors and thus in opposition to the existing medical paradigm. A prime example is the Swedish group Anti-Handikapp. Activist Vilhelm Ekensteen’s book ‘In the Backyard of the People’s Home’ (På folkhemmets bakgård) from 1968 and Anti-Handikapp demanded the breakdown of societal and attitudinal barriers by adapting the existing welfare system to the needs of all citizens, a ‘society for all’. In 1972 this idea was pursued further in the Swedish disability organizations’ political program of the same name, and four years later also in the governmental report ‘Culture for All’ (Kultur åt alla). Similar notions of disability also resonated in the other Nordic countries, for example the Finnish self-advocacy association Threshold (Kynnys), founded by disabled university students in 1973.

PICTURE: The Equality March in Reykjavik 1978. Photo: Newspaper article “A turning point in the fight for equality for all disabled persons in the country”, in: Þjóðviljinn, 20 September 1978, p. 5 (Tímarit.is).

The public visibility of disability should also be mentioned, which spanned newspaper articles, exhibitions, interviews on the radio and television, protest marches and demonstrations. In 1976 Swedish organizations of the blind and the deaf organized a demonstration in Stockholm that attracted about 8,000 participants. Two years later, a staggering 10,000 to 15,000 demonstrators gathered in Reykjavík for a so-called ‘Equality March’. Gradually the activists’ demands influenced new legislation that included welfare services, building regulations, technical and medical aid, public transportation and job counseling. Disability representatives also gained a political voice through seats on disability councils and committees.

1981: The International Year of Disabled Persons

The International Year of Disabled Persons (IYDP), organized by the United Nations in 1981, added further momentum to the disability rights movements. The IYDP slogan ‘full participation and equality’ resonated well with the Nordic approach to disability and hopes were correspondingly high. Across the region as well as internationally, national IYDP committees with politicians, public officials and representatives of disability organizations organized a range of festivities throughout the year:

- Swedish disability rights organizations continued their cooperation with politicians and authorities with a national disability survey, cultural events and other activities. However, this relationship was strained by threatening austerity measures culminating in a large demonstration of disability rights activists in Gothenburg with approx. 9,000 participants.

- When the Norwegian government hesitated to give disability a prominent political platform and tried to limit the IYDP to sports and leisure activities, disability organizations sought out new alliances with other civil society organizations and the general public.

- The IYDP in Denmark took a more radical turn as a new law on income-dependent disability assistance was seen to threaten disabled people’s self-determination. The disagreement concluded with a split between the national committee, headed by the Minister for Social Affairs, and a very vocal and influential ‘alternative’ committee established by the Association of Disability Organizations (De Samvirkende Invalidorganisationer, DSI). There were also a number of events in Greenland that dealt with the set-up of local disability care.

- In Finland, the year was dominated by the Veteran Association’s focus on care and service provision on the one hand, and the more activist approach of the Threshold Association on the other. Four regional disability projects were conducted: education of Swedish-speaking Finns in Vaasa province, social and health services in Oulu province, employment and housing in Kuopio province, and training opportunities in North Karelia province.

- In Iceland, the impact of the 1978 ‘Equality March’ still reverberated in early 1981 when politicians, union leaders and disability rights activists organized a well-attended public meeting on equality and labor market integration. They also organized public events and discussions on legal reforms.

PICTURE: Visual interpretations of disability on stamps issued by Nordic governments for the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981. Collage: Anna Derksen.

Although many disability activists afterwards voiced their disappointment that not more had been achieved, the year also yielded positive results. Firstly, national action plans and policy guidelines ensured a continued discussion of the topic and its legal implementation. Secondly, self-advocacy organizations gained visibility and generated public interest in their concerns. And thirdly, disability was increasingly seen as a human rights concern that demanded attention and alliances across social, ideological and administrative borders.

Developments since the 1980s

The 1980s saw a number of legal reforms that further defined the rights of people with disabilities. Special institutions and public welfare services were devolved, while care services became more individualized. A landmark reform in this regard was the Swedish Act concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (LSS) of 1994, which introduced a personal budget for severely disabled persons and personal assistance for daily activities, housing, and work, and has since inspired many other countries to implement similar laws. Other important innovations were the implementation of anti-discrimination laws in the 1990s and the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities since 2006.

Today the Nordic disability movements are somewhat fragmented, but their past efforts have made vital contributions to putting the situation of people with disabilities and other marginalized groups on the political agenda, embedding disability in the public consciousness as a social and human rights issue both nationally and internationally. Nordic disability organizations are also sharp critics of current challenges, like economic austerity measures and an increasing marketization of disability care, and they continue to play an important role in policy-making and social debate as well as in the monitoring of disability legislation.

Further reading:

- Bengt Erik Eriksson and Rolf Törnqvist, eds., Likhet och särart. Handikapphistoria i Norden [Equality and difference. Disability history in the Nordic countries] (Nynäshamn: Handikapphistoriska föreningen, 1995).

- Greta M. Cederstam, ed., Vägen till människovärde. Några drag ur nordisk handikapphistoria åren 1945-1985 [The road to human dignity. Some features from Nordic disability history in 1945-1985] (Vällingby: Nordiska nämnden för handikappfrågor, 1990).

- Karl Grunewald, Från idiot till medborgare. De utvecklingsstördas historia [From idiot to fellow citizen. History of intellectual disability] (Stockholm: Gothia förlag, 2008).

- Rannveig Traustadóttir and Kristjana Kristiansen, eds., Gender and Disability Research in the Nordic Countries (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2004).

- Snæfriíður Thóra Egilson, Berit Berg and Rannveig Traustadóttir, eds., Childhood and Disability in the Nordic Countries. Being, Becoming, Belonging (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).