Drama in Iceland, 1900-2000

This is the second Quick Read on drama and it focuses on Iceland.

Despite the formation of the Rekjavík Theatre Company in 1897, a National Theatre (Þjóðleikhúsið) was not established until 1950 and the Company did not become fully professional until 1963. The problematisation of values and the critique of materialism became a recurring theme in the drama of the 1960s and 1970s. Social and economic change figured prominently in the 1980s and 1990s with, for example, Birgir Sigurðsson’s Day of Hope (Dagur vonar) about a working-class family and Ólafur Haukur Símonarson’s 'The Sea' Hafið (1992) about the fishing industry. Interestingly, Erlingur E. Halldórsson’s The Calculator (Reiknivélin) written all the way back in 1963 dealt with the presence of foreign troops in Iceland; American troops, who came to Iceland after the Second World War, remained in Keflavík until 2006.

With its very small population, rural economy and position as a Danish colony, Iceland in the nineteenth century had no central theatre, and any plays by Icelandic authors would receive their first performance in Copenhagen. But by the end of the century, amateur theatre groups were flourishing, and in 1897 the Rekjavík Theatre Company (Leikfélag Reykjavíkur) was formed to encourage the writing and production of drama in Iceland.

Iceland gained its independence from Denmark in 1944 and the National Theatre (Þjóðleikhúsið) was established in Reykjavík in 1950, but despite Agnar Þórðarsson’s Þeir koma í haust (Autumn Return) (1955), a historical play about the settlers in Greenland, there was little in the way of new Icelandic drama until the 1960s. To some extent, this new wave was influenced by developments in European drama, but more important were the economic, social and cultural changes in Iceland as more and more people moved to urban areas, notably Reykjavík, thus severing their links with rural communities and their sets of values. The problematisation of values and the critique of materialism became a recurring theme in the drama of the 1960s and 1970s, much of it influenced by the work of Brecht. Moreover, the Reykjavík Theatre Company became fully professional in 1963, a number of fringe theatre groups emerged, and state television was established in 1966. The People’s Theatre (Alþýðuleikhusið, 1975-93) had a socialist political agenda. A children’s theatre was established in 1990.

Jökull Jakobsson wrote dramas for the stage, radio and television, his ear for everyday speech contributing to the success of Hart í bak (Hard a Port) (1962). Halldór Laxness, best known as a novelist, wrote several dramas in the 1950s and 1960s including Strompleikurinn (The Chimney Play) (1961), about the pretence of theatre, and Þrjónastofan Sólin (The Knitting Workshop ‘The Sun’) (1966), about the international situation.

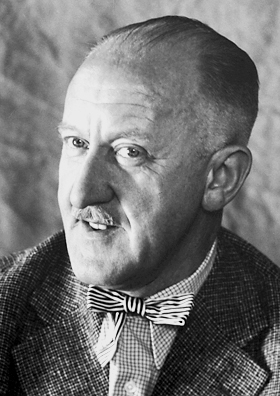

PICTURE: Portrait of Halldór Laxness (1902-1998) taken in 1955, the same year he received a Nobel Prize in Literature. Picture: Nobel Foundation, Public Domain.

Erlingur E. Halldórsson’s Reiknivélin (The Calculator) (1963) considers the presence of foreign troops in Iceland (after the end of the Second World War, American troops were to remain at Keflavík until 2006), while a play such as Hversdagsdraumur (An Everyday Dream) (1972) makes innovative use of the medium of theatre to problematise the relentless march of materialism. The critique of materialism is also at the forefront of dramas by Guðmundur Steinsson such as Stundarfriður (A Brief Respite) (1979), a major international success. Structurally inspired by classical music, Oddur Björnsson’s dramas convey bleak perspectives on the modern world, the three soldiers searching for a war in 13. Krossferðinn (The Thirteenth Crusade) (1993), failing to find one but still having a destructive impact.

Svava Jakobsdóttir’s documentary Hvað er í blýhólknum? (What’s in the Corner Stone?) (1971) was the first Icelandic drama to deal with gender equality; Steinunn Jóhannesdóttir’s Ferðir Guðríðar (Guðríður’s Travels) (1996), about an Icelandic woman abducted by pirates in the seventeenth century, similarly testifies to the appeal of documentary drama. The first Icelandic drama to focus on homosexuality was Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s Ástarsaga 3 (Love Story 3) (1998). Social and economic change continued to figure prominently, as in Birgir Sigurðsson’s Dagur vonar (Day of Hope) (1986), about a working-class family, and Ólafur Haukur Símonarson’s Hafið (1992) (The Sea, publ. 2001), about the fishing industry. The mother-daughter relationship in Hrafnhildur Hagalín’s Haegan, Elektra (2000) (Easy Now, Electra, publ. 2001) provides an opportunity to explore the medium of theatre; and the medium is also problematised in Árni Ibsen’s Himnaríki (1995) (Heaven, publ. 2001) with its dual action and two sets of audiences that change places at the interval.

PICTURE: Portrait of Svava Jakobsdóttir (1930-2004) from nordicwomensliterature.

This article has been published posthumously.

Further reading:

- D. Neijmann, ed., A History of Icelandic Literature. (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press; 2006).