Impact bonds in the Nordics

An impact bond is a financial contract between public and private stakeholders with the aim of solving societal problems. Impact bonds remain experimental but they have taken hold in the Nordic countries where 'impact' has included better educational outcomes, integration of immigrants and prevention of type 2 diabetes. While the Nordic context may prevent some of the risks of impact bonds that have been identified in research, impact bonds may still give rise to several challenges in the Nordic region.

What are impact bonds?

An impact bond is a public-private partnership where the aim is to create a particular social or environmental impact. Impact bonds have increased in popularity since the late 2010s as a way of pursuing both economic gains and evaluated impacts by combining the broader logic of impact investing with public policy-making. The impact can be on, for example, unemployment, ex-prisoners re-offending, green infrastructure, social exclusion, or occupational well-being.

The most common use and name for the impact bond is the SIB (social impact bond), but EIBs (environmental impact bonds) and DIBs (development impact bonds) have also been implemented. Additionally, terms such as social outcomes contracts (SOC) and Payment-by-Result schemes (PbR) have been used for the same kind of projects. Adding these up, over 250 projects have thus far been carried out in over 30 countries (according to the Government Outcomes Lab).

How do impact bonds work?

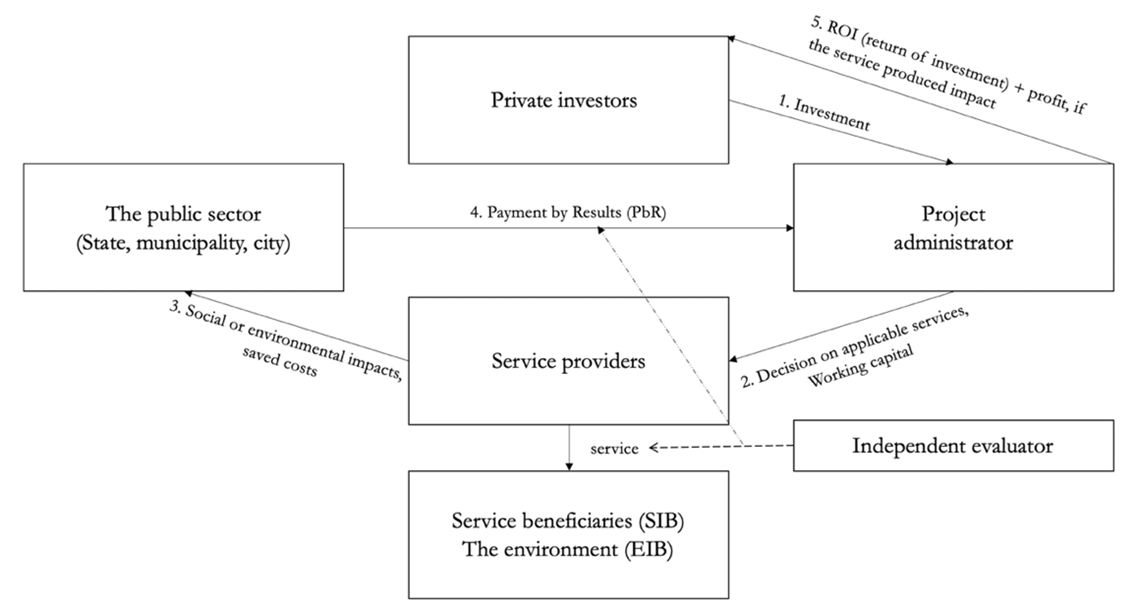

Private investors provide the starting capital for projects and they are only paid back by a public sector actor, with profit, if the projects have achieved the impact that was specified beforehand. An outside evaluator is also usually included as a stakeholder, as well as a project administrator who acts as an intermediary between stakeholders, including the service providers – businesses or NGOs – whose job it is to generate the impacts.

Through this collaboration, impact bonds are intended to provide benefits for all the stakeholders by creating a 'win-win-win-situation' while generating social or environmental impacts. The investors are to do societal good, public sector actors are to save taxpayers' money, and service providers are to receive flexible funding.

Figure 1: Impact Bond Structure

Impact bonds remain experimental and controversial, despite several claims about the benefits and advantages, as there are no clear results about their success (see Tan et al, 2021). They are thus simultaneously celebrated and questioned. Do they really provide pre-emptive, efficient and mission-based improvements that save the taxpayer money as part of 'transformative investment'? What kind of macro-scale implications might they have (see Chiapello and Knoll, 2020, for more on this)? These are relevant questions for any impact bond and the Nordic context also presents further variables in answer to these questions.

Impact bonds and the Nordic countries

The development of impact bonds was originally particularly rooted in the policy spheres of liberal welfare in the United States and the United Kingdom, yet they have also reached many other places worldwide, including the Nordics.

While the welfare state has traditionally had a strong role in solving societal problems in the Nordic countries, the role of private sector actors has also been increasing over the last couple of decades. Accordingly, there have been over 20 impact bonds carried out or planned in Finland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and Finland has even been the EU country in which most resources have been allocated to impact bonds thus far (according to the Government Outcomes Lab). The objectives of Nordic impact bonds have included, for example:

- better educational outcomes for children and young people in the Swedish Norrköping-SOC,

- increasing the ability of young people to deal with stress and interact in the Norwegian Lier municipality hybrid SIB scheme,

- the employment and integration of immigrants in the Finnish Koto-SIB,

- the prevention of type 2 diabetes in three places in the Nordics – in the Stockholm region Health Impact Bond, the Aarhus SIB and the Finnish T2D-SIB.

Projects like the above seek to tackle social problems mostly with interventions such as employment training or personalized lifestyle coaching, and they purportedly bring together stakeholders across sector borders. By doing so, it is argued that they complement welfare state actions with the help of the private sector and thus are able to deliver the 'win-win-wins'.

Risks of impact bonds

This article is not intended as a comprehensive review of impact bonds, but merely a short overview. Nevertheless, it is possible to say that the literature concerning impact bonds provides several noteworthy reasons to remain sceptical. These reasons have been identified in existing research and include the difficulty in evaluating the impact of impact bonds, their high transaction costs, and their 'policy risk'; the possibility of government and what it focuses on changing, risking the necessary long-term commitment to impact bonds (see Tan et al. 2021, as well as James Williams' article from 2020).

The instigators of impact bonds also do not generally appear to seek to change the structural relations of societal ills – as it is possible to argue that progressive taxation has historically been able to do in the Nordics, for example. Root causes of societal problems such as socio-economic inequality may go unaddressed or even be accelerated, as noted by studies that have shown how it is usually marginalized people in impact bonds that are required to take on more responsibility about their own well-being and who are, in this way, made into an ’investment proposition’ for those who are better off (see for example Wirth 2020, as well as Neyland's 2018 paper 'On the transformation of children at-risk into an investment proposition: A study of Social Impact Bonds as an anti-market device').

Several other more macro-scale risks can be pointed out as well. In some cases, investors have been able to generate profits from projects that have not been successful in providing the expected savings for the public sector, removing the narrative of a plausible 'win-win-win' (see Tse & Warner's 2018 paper on the financialisation on early childhood). More broadly, impact bonds have been connected to short-termism in aiming for clear, calculable results instead of any kind of long-term policy vision - as set out in Berndt & Wirth's article in Geoforum from 2018.

Impact bonds have also been seen as playing a role in a larger trend of financialization – the growing societal power of financial actors (see Sinclair et al. 2021). This can undercut the basic tenets of democratic decision-making and affect economic (and other) equality if private investors are the ones who get to choose how to provide welfare and to whom, while making profit at the same time.

’Stretching’ impact bonds in the Nordics

'Stretching' the impact bond has been used to refer to how some features of impact bonds have been changed in order for them to fit better in different societal, political and issue-related contexts (see Christina Economy et al's article from the International Public Management Journal in 2022). Such adaptation has become more or less a standard feature in the Nordic countries – perhaps as another route for seeking to achieve a Nordic model. Might such stretching indeed help avoid the identified risks of impact bonds?

In Denmark, for example, the 'Growth with a Social Bottom Line' project, aiming to help small and medium-sized enterprises employ 'vulnerable citizens', considerably stretched the usual roles of actors in impact bonds, as Andersen et al. conclude in their study (2022). Public rather than private funding provided the starting capital for the project, and service provision was not outsourced to an external provider, but was carried out in close collaboration with public authorities. ''Similar dynamics have also been apparent, for example, in two projects concerning occupational health. In the Swedish SOC, the municipalities of Botkyrka and Örnsköldsvik chose to act as financers themselves, while in the Finnish Tyhy-SIB the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra acted both as a facilitator of the project as well as one of the investors.

These kinds of actions have at times been criticized as diluting the SIB effect, since in them some key notions and roles of the impact bond structure are changed. But perhaps such versions of impact bonds – influenced by the Nordic context of a strong welfare state – might even provide some solutions to the criticism that has been voiced against impact bonds elsewhere? This indeed comes close to the view provided by Andersen et al.'s study, yet there is thus far only limited evidence on the question.

Interestingly, it has not only been the form, but also the content of impact bonds that has been stretched in the Nordics. For example, in September 2021, a 10 million dollar Refugee Impact Bond (a DIB) funded by the IKEA Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation and Norad (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) was announced, to be carried out in Jordan and Lebanon. The project is to deliver a 'vocational, entrepreneurship, and resilience-building programme' that is to 'enable people affected by conflict to become self-reliant'. It is surely few who are as such against the idea of helping vulnerable people to achieve economic stability. Yet the 'micropolitical' logic and the global power relations inherent in the scheme can, and indeed need to be, questioned: Should international development programmes need to become profitable for them to be taken up?''

Another interesting case of stretching is the Nutrient-EIB, an environmental impact bond planned for Southwest Finland, which seeks to build a market for recycled nutrients. If successful, the Nutrient-EIB would diminish the eutrophication of the Baltic Sea and reduce the use of mineral-based fertilizers which are based on limited and geopolitically risky resources, especially phosphorus. However, I and my co-authors conclude in our study that, while basically all aspects of the EIB have been viewed positively by its stakeholders, things like alignment with the EU agricultural policy and regional equity have proven to be barriers that are hard to overcome (see the paper by the author, Matti Pihlajamaa and Maria Åkerman from 2022). The benefits of impact bonds may thus be difficult to achieve unless they are part of wider policy efforts, and the inclusion of private finance might, in the end, not in itself equal to achieving results that would push sustainability transitions.

The future of impact bonds in the Nordics and elsewhere?

While impact bonds remain niche both in the Nordics as well as globally, there has been a lot of hype about them among 'policy entrepreneurs' such as innovative foundations, think tanks and socially-minded investment companies, with a growing interest among researchers, too. They have, however, arguably yet to live up to their promises as their results have not been clear, and as there seems to be a lot of risks and problems involved in implementing them. Perhaps it will take more time to understand the best way to utilize impact bonds, since time is not only needed to experiment with any new policy instrument, but there is also an especially lengthy timescale of three to ten years needed from when impact bonds are first carried out to when they are evaluated. Some stretching may thus indeed be necessary before finding best practices. Yet it is unclear if even this will help.

Whether one remains sceptical or optimistic, reviewing impact bonds provides a way of understanding some of the contemporary societal shifts undertaken by states, including Nordic ones. Impact bonds may be forgotten after a time. Some aspects of impact bonds will, however, most likely become, and have already become, absorbed into public policy, including things like responsibilizing policies, increased impact evaluation, and the construction of markets as a way to address collective concerns.The Nordic context of implementing impact bonds, or similar policy efforts, may prevent worst-case scenarios by providing more of a middle way between financial and welfare state logics. Whether, how, and to what extent Nordic states should seek for such a compromise – and see its citizens or the environment primarily or overall as investments, for example – is another question. While there are many reasons to remain critical, there definitely remains a need to find new kinds of solutions to problems like climate change and its societal consequences, which will only accelerate in the coming years.

Further reading:

-

D. Neyland, 'On the transformation of children at-risk into an investment proposition: A study of Social Impact Bonds as an anti-market device'. The Sociological Review 66, 3 (2018) pp. 492–510.

-

E. Chiapello, and L. Knoll, 'Social Finance and Impact Investing. Governing Welfare in the Era of Financialization'. Historical Social Research 45,3 (2020) pp. 7–30.

-

M.M. Andersen, R. Dilling-Hansen and A.V. Hansen, 'Expanding the Concept of Social Impact Bonds'. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13, 3 (2022) pp. 390–407.

-

O. Tiikkainen, M. Pihlajamaa, and M. Åkerman 'Environmental impact bonds as a transformative policy innovation: Frames and frictions in the construction process of the Nutrient-EIB'. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 45 (2022) pp. 170–182.

-

S. Tan, A. Fraser, N. McHugh and M. Warner, 'Widening perspectives on social impact bonds'. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24, 1 (2021) pp. 1–10.

Links:

- Government Outcomes Lab: Impact Bond Dataset

- Article with diagram explaining Social Impact Bonds, entitled 'Sitra and Me-säätiö launch first Social Impact Bond in Finland', The Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, 23rd November 2015.

- Research project: Neoliberalism in the Nordics: Developing an Absent Theme