Principles of welfare distribution: A comparison between Nordic and European citizens

Selected figures for 2018 and 2019 suggest that there is less inequality and a lower risk of poverty in the Nordic states than elsewhere in Europe. But when it comes to the type of welfare measures used and people’s preferences for the underlying principles of welfare services, the Nordics are surprisingly similar to many other countries in Europe.

Selected Eurostat figures for 2018 suggest that Nordic welfare states might be more similar to the rest of Europe with respect to welfare expenditure measures than is often assumed, although they do appear to produce better social outcomes in terms of less social inequality and a lower risk of poverty. Existing social policies and the institutions that administer them often create norms on what is desirable in society and how things ought to be organized, and this has a knock-on effect on what type of welfare measures people prefer. Following this logic, it could be expected that citizens in the Nordic countries should express a preference for equality and universalism when it comes to welfare distribution. However, based on data from the European Social Survey in 2018/19 concerning preferences grouped under the three principles of equality, equity and need, Nordic people are more similar to those in other European countries than may first appear.

The type of welfare state effects attitudes towards welfare

In a European context, three types of welfare states are traditionally put forward: social democratic (strongly universal, the Nordic countries), conservative (social insurance based, for instance Germany) and liberal (targeted and selective benefits, for instance the United Kingdom). It is also often assumed that people prefer welfare to be distributed in line with how it is predominantly organised in the welfare state of their country of residence. According to the literature on how social policies or institutions impact public preferences, welfare states have a ‘norm-shaping function’. Welfare state policies tend to set down norms on what is desirable in society and how things ought to be organised. Citizens then arguably adopt these normative motivations and express preferences or opinions that are in line with them. This leads to different clusters of countries where there are particular attitudes to welfare – referred to in the literature on public opinion as ‘worlds of welfare attitudes’. If this is indeed true, it could be expected that the Nordic countries would most likely form a separate cluster built on support for the ideals of equality, universality and broad redistribution. Yet, is this Nordic exceptionalism really visible in the data? Or is it in fact the case that these countries are more similar to other European states after all?

How do the Nordic countries score on social indicators?

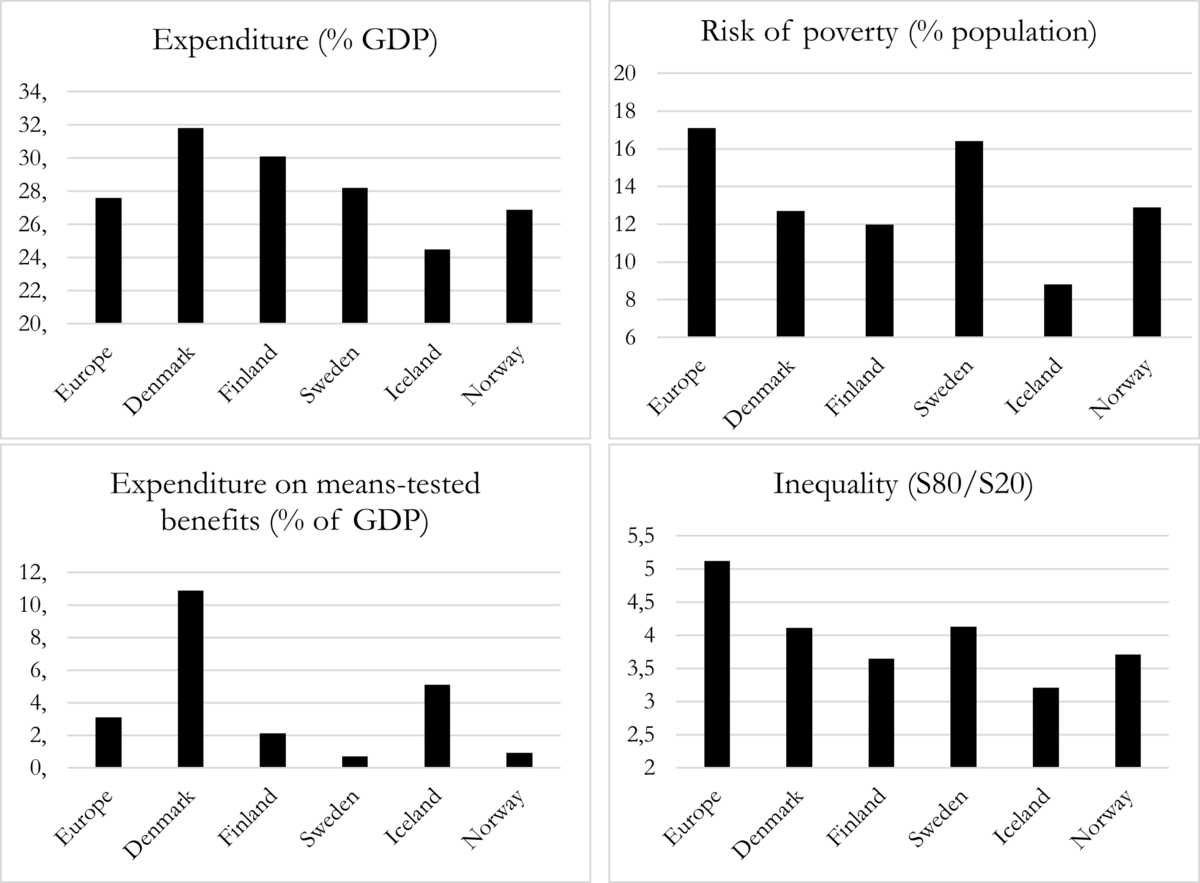

Before I turn to people’s attitudes, it is worth exploring how the Nordic social security systems score relative to the European average on a number of social indicators. First of all, social expenditure (spending on welfare-related benefits and services) offers an indicator of the extent to which states are concerned with the standard of living of various vulnerable groups. It can be seen from the graph showing statistics from 2018 that, except for Iceland and Norway, all Nordic welfare states indeed have higher social spending than the European average. Yet, the differences are not as pronounced as might be expected.

A second indicator of welfare state initiatives is measured by the percentage of expenditure spent on means-tested benefits, which are only granted to those with insufficient resources. We can see that Denmark and Iceland spend considerably more on selective benefits than the European average and the other Nordic countries do not differ so much from the rest of Europe. Contrary to expectation, then, the Nordic countries do not embrace universalism as much as may be expected.

However, when measuring the outcomes of welfare measures, there does seem to be clearer Nordic specificity. All of the Nordic countries score considerably lower on the risk of poverty and the degree of inequality (measured by the (S80/S20) ratio between the income received by the top 20% earners and that of the lowest 20% earners in a country) than the European baseline. This illustrates that they do comparatively seem to achieve an effective redistribution of income and wealth.

These indicators do not account for qualitatively distinct types of policies and other complicating factors, such as benefit generosity in Nordic welfare states, and hence make it difficult to offer a full comparison to other European social security systems. However, this quick review of the figures still suggests that Nordic welfare states might be more similar to the rest of Europe with respect to welfare measures than is often assumed. Yet, the social outcomes that they achieve do appear to be more exceptional.

The link between the type of welfare state and public opinion: equality, equity and need

These figures – and other evidence – suggests that the Nordic welfare states are still by enlarge supportive of the ideas of equality and universality (or they at least achieve these desired norms to a relatively strong degree). This being so, it could mean that citizens are also more supportive of solidarity and equal outcomes for everyone. In light of the different attitudinal clusters, this should mean that the Nordic countries make up a separate ‘world of attitudes’ that differs from countries with other types of welfare organization.

To test this, I looked into people’s preferences for three different types of how the distribution of income and wealth are organised in society, based on data from the European Social Survey round 9 (2018/2019) in 29 countries, namely, equality, equity and need. Each of these principles can be interpreted as also corresponding to one of the three main different types of welfare system that exist in European countries:

- First of all, I looked into support for equality, which is the main organising principle of the Nordic social democratic welfare states and focuses on an equal distribution of resources. It is measured by asking people whether they believe “A society is fair when income and wealth are equally distributed among all people”.

- Second, the principle of equity, which is usually dominant in conservative welfare countries like Germany and Belgium, postulates that hard work and contributions to the system should determine income or wealth differences. The survey item asks people whether they think “A society is fair when hard-working people earn more than others”.

- Last, the principle of need was examined, which is a predominant factor in distribution in liberal welfare states like the United Kingdom, and generally only caters for the living standards of those most in need (like the poor). The indicator for this item asks whether individuals believe that “A society is fair when it takes care of those who are poor and in need regardless of what they give back to society”.

Based on the support for these principles, different attitudinal clusters can be discerned that might or might not mirror welfare state organisations.

Although welfare attitudes are inherently multidimensional and can encompass many other components as well (like the degree of redistribution, the efficiency, the implementation of policies, …), these three principles (equality, equity and need) link nicely to different fundamental types of distribution. So, despite only capturing one overall aspect of people's opinions on welfare, they helpfully cut to the core of welfare state organisation, and are useful as broad and basic principles to study attitudes comparatively across Europe.

No distinct attitudinal cluster in the Nordics

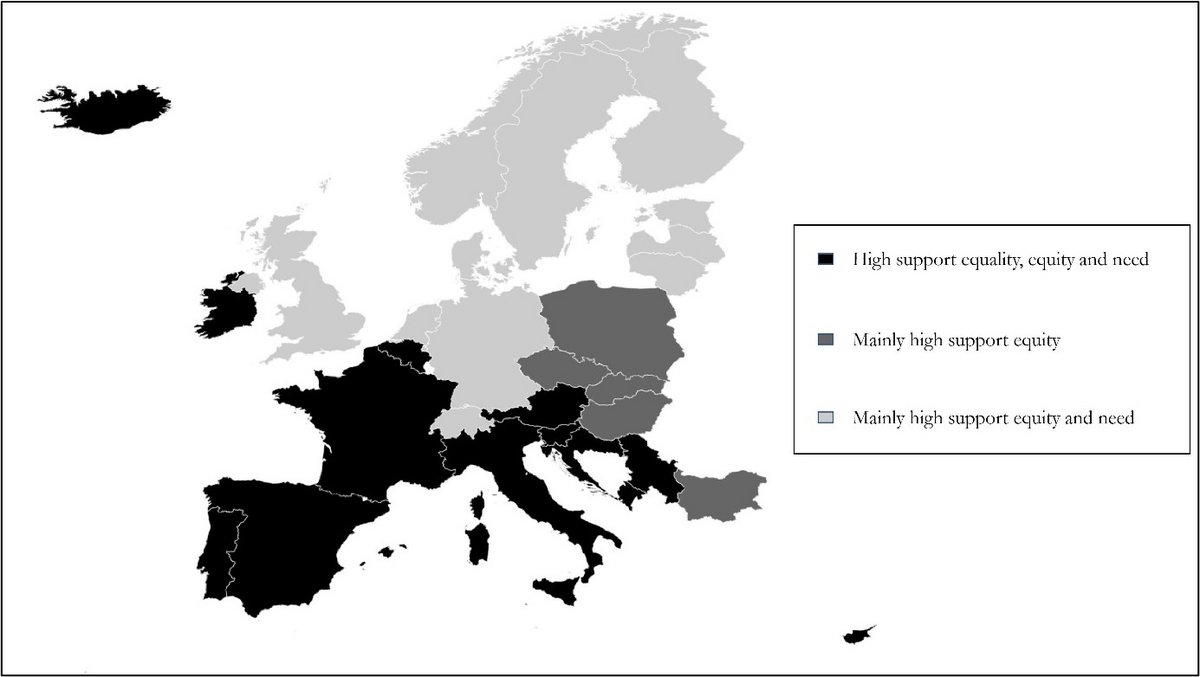

The figure displayed below shows the clustering of European countries according to their support for these three distributive ideas: equality, equity and need. I discovered three clusters:

- A group of countries with a majority of individuals who simultaneously show a high support for granting equal resources to everyone (i.e. equality), rewarding hard work (i.e. equity) and providing resources to those with insufficient material capabilities (i.e. need);

- A group of countries with the strongest representation of individuals showing only a high support for equity; and,

- A cluster of countries with the highest prevalence of a high support for equity and need.

Note that there is still of course heterogeneity within these clusters, but that they are merely characterised by a clear overrepresentation of support for one or more of the redistributive principles. For instance, the cluster with strong representation of support for equity just has the highest share of individuals supporting equity, but this does not imply that there are not still groups favouring equality or need (they are just considerably less prevalent).

According to the normative welfare state framework – that is, that people’s preferences often mirror the norms which already exist - and the idea that the Nordics are in an exceptional group of their own, the Nordic countries should arguably form a separate cluster that at least shows high support for equality (so be in the first group). However, the Nordic countries do not only fail to constitute a separate group, but equity and need are in fact preferred. Except for Iceland, all the other Nordic countries do nevertheless belong in the same attitudinal cluster - although several continental countries are equally part of this ‘world of attitudes’. These results question the purported attitudinal distinctiveness of the Nordic countries.

At the same time, they may also question the well-established assumption that there is a strong link between existing welfare state structures and public preferences. However, it is important to note that these clusters of countries make an abstraction of the heterogeneity of social policies, public preferences and types of distributions within countries. It has been argued that it could be much more useful to study welfare distributions and their link to public opinions on a meso-level (namely at the level of concrete welfare measures or domains), instead of on this high, overarching level. It is interesting to consider whether classifications, including the welfare regime typology, remain useful in a contemporary setting, or whether the trade-off between simplification and reduction in heterogeneity is simply too large. That said, an overview is undoubtedly useful as a starting point to provide a quick glance at cross-national differences and to offer insight into the question of Nordic exceptionalism.

Further reading:

-

P. Taylor-Gooby, B. Hvinden, S. Mau, B. Leruth, M.A. Schoyen, & A.Gyory, ‘Moral economies of the welfare state: A qualitative comparative study’, Acta Sociologica 62, 2 (2019) pp. 119-134.

-

Arno Van Hootegem, ‘Worlds of distributive justice preferences: Individual-and country-level profiles of support for equality, equity and need’, Social Science Research (2022) pp. 1-14.

-

Lyle Scruggs & Gabriela Tafoya Ramalho, ‘Fifty years of welfare state generosity’, Social Policy & Administration (2022) pp. 1-17.

-

H. Ervasti, K Ringdal, Torben Fridberg & Mikael Hjerm, eds, Nordic social attitudes in a European perspective (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008).

-

T. Reeskens & Wim van Oorschot, ‘Equity, equality, or need? A study of popular preferences for welfare redistribution principles across 24 European countries’, Journal of European Public Policy 20, 8 (2013) pp.1174-1195.