The Nordic response to the Great Depression – an economic approach to the Corona crisis?

A look back at how Sweden and Finland dealt with two key crises in the twentieth century may be enlightening during the current Corona crisis. Firstly, the depression in 1930s, which led to Keynesian interventionalism - with some key differences - brought with it a series of steps throughout the following decades in both countries. Secondly, the global oil crisis in 1970s, when the two countries embraced an approach which heavily steered their national economies into becoming guarantors of smooth-functioning capitalism. While their responses were similar to other western democracies, certain aspects were divergent. There are similarities between the economic policies leading up to 1930s and the post-Bretton Woods capitalism that has lasted since 1970s. The current corona crisis may provide an opportunity for political elites in the Nordics as elsewhere to choose similar paths to back then, namely, either a Keynesian-type of countermovement to free market capitalism, or inward-looking xenophobic nationalism.

Modernising capitalism underpinning mass employment, 1850-1920s

Employment became a core concept in Sweden and Finland after the industrial revolution and modernising capitalism produced the phenomenon of larger-scale waged work in the last decades of the 19th century. Experiences elsewhere, for example, in the English countryside, in the second half of the 19th century saw the endorsement of capitalism. This was of course underpinned by long-standing principles of the Enlightenment and technological development. Karl Polanyi has referred to the period from 1850 to 1930 as "the self-regulating market” of the world economy.

In Sweden and Finland, the livelihood of the working population, which had emerged at more or less the same time, became endangered especially during economic downturns. But here, in Sweden and the Grand Duchy of Finland (the latter being a part of the Russian empire until 1917), unemployment was more of a societal question and, that being so, municipalities already started to arrange relief work in a series of steps from the mid-1880s.

The Great Depression of 1930s and Keynesian regulation in Sweden and Finland

In the aftermath of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the rise of capitalism and the faith of economic liberalists in a self-regulating market contributed to the birth of mass unemployment, something which is acknowledged as being a key factor in the rise of fascism in several European countries. This was avoided in Sweden by increasing public investment which was based on a counter-cyclical expansionist economic policy endorsed by the economists of the Stockholm School and Finance Minister Ernst Wigforss, who had been acquainted with the similar ideas of British Liberals and the economist J.M. Keynes. Conversely, no signs of wider counter-cyclical economic policy emerged in Finland at that time despite the majority of the workforce suffering from unemployment, at least for a period during the Great Depression. During the 1930s, the support of fascism increased in the country, which had only gained independence from Russia during World War I. Despite this, parliamentary democracy was preserved, even if trade union influence was restricted and The Communist Party of Finland was illegal as a result of the civil war in 1918.

PICTURE: An increase in fascism in Finland led to e.g. the Communist Party of Finland being made illegal from 1918-1944. Photo: Communist Party Logo, Fair Use.

A form of Keynesianism was practised in both Sweden and Finland from after the Second World War until the mid-1970s. Here, undoubtedly similar to elsewhere, it broadly meant state intervention in the economy, financial market regulation and the favouring of low interest rates in order to channel scarce national capital into productive investments. It also meant practising a counter-cyclical fiscal policy in Sweden, unlike in Finland at that time. In Sweden, influential Social Democrats supported the idea that increasing demand for public services and the productivity of private companies consolidated each other in shaping societal development and a policy of full employment. The Finnish Social Democrats were both weaker than their Swedish counterparts and didn’t favour counter-cyclical financial and monetary policy. However, they too urged the maintenance or achievement of full employment.

PICTURE: Swedish politician Ernst Wigforss (1881-1977) was considered one of the most important thinkers behind the policies of the Social Democratic Party throughout much of the early 20th century. Photo: Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain.

Irrespective of the differences between the two countries, it is clear that the strong welfare state in both Sweden and Finland was built around the characteristics of economic growth, rational planning, and the cooperation between major government and labour market parties in Sweden and Finland.

The global oil crisis in 1970s and the rise of neoliberalism and the competition state

Like many other parts of the world, neo-liberalism and the increasingly globalising world economy challenged post-Second World War welfare state Keynesianism in Sweden and Finland in the 1970s. The consequences of the global oil crisis weakened the support of Keynesianism and consolidated the ideas of the neoliberals. The latter had intentionally constructed a recognisable set of corporation- and capital-friendly doctrines, which led to a reliance on market competition with respect to almost every societal question that had occurred since the 1930s.

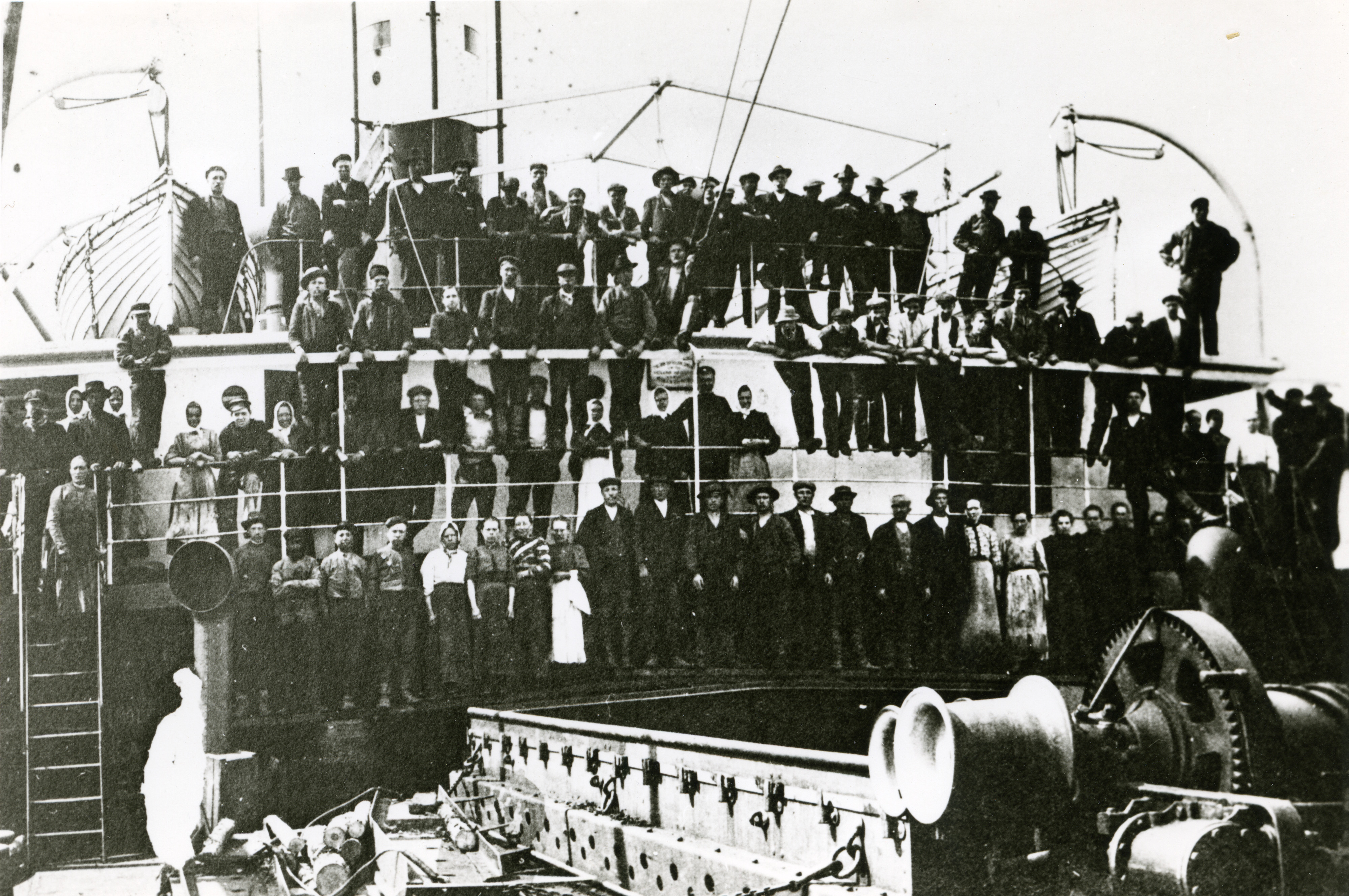

PICTURE: The reaction of both Finland and Sweden to the global oil crisis of 1970s was different to that of the response to the Great Depression and, since then, post-Bretton Woods global capitalism has dominated in an arguably similar fashion to before the 1930s. Photo: Rauma-Repola oil rig in Mäntyluoto, Finland, creative commons (finna.fi).

In Sweden, the goals of the mid-1970s to raise the employment rate and guarantee jobs for all were replaced in the early 1980s by the primacy of an anti-inflationist policy in the manner of neoliberal monetarist economic theory; the focus was no longer on permanent full employment. This was compatible with Finland’s economic policy from the second half of the 1970s. A series of steps in both countries followed towards liberating the capital markets from that time until the early 1990s.

The globalisation of capital enabled the use of an 'exit' option by owners of capital in an era when states and other geographical entities competed for private investment. At the same time, political actors sought market acceptance of their politics by trying to justify their actions publicly in ways which satisfied dominant market actors. Under these circumstances, the political sphere became increasingly subordinate to the economy. Capital outflow and the following high interest rates could only be blocked by introducing public sector retrenchment packages. Furthermore, increasing employment became dependent on economic growth and the competitiveness of companies during and after the profound economic depression in Sweden and Finland in the 1990s.

The consequence of this was that a 'market acceptance strategy' was adopted which meant practising not only an anti-inflationist economic policy, but also policies to moderate wages policy, stabilise currency as well as a strict financial policy. This was in line with turning the goal of full employment into one where unemployment should be halved in Sweden and Finland, a policy that was adopted in the 1990s. Consequently, the unemployment rate rose to 15% in Finland and 9% in Sweden in the 1990s.

A different type of neoliberalism?

Many are not aware that Finland and Sweden at least partly embraced neoliberalism. This did not mean that companies and the markets themselves were the driving forces behind the economy in the manner of classical liberalism. In fact, it was first and foremost the role of the state and international institutions to guarantee the existence of a stable market society, the free flow of capital across national boundaries, and market discipline through flexible exchange rates.

PICTURE: The political sphere has became increasingly subordinate to the economy in Finland and Sweden, as elsewhere. Photo: Parliamentary chamber of the Finnish Parliament. Flickr, fair use/Hanne Salonen.

Sweden and Finland did not solely commit to a neoliberal or monetarist approach, even though they favoured neoliberal capital market liberation and partial privatisation. Importantly, they also labelled the reason behind unemployment as “structural”; this was in line with a European version of mainstream economics (termed neoclassical synthesis), which blamed the institutional welfare state and labour market rigidities for imposing involuntary unemployment. Keynesian economic regulation was also replaced in Finland and Sweden by neocoporatist innovative restructuring and labour market flexibility strategies, as well as neostatist technological investments.

At the same time, the role of the state was transformed from one which steers the economy actively, into one which seeks only to be a guarantor of smooth functioning capitalism and constructing attractive transnational communities to capitalist investors. This replaced the Nordic post-war virtuous circle between growth, equality and democracy. This happened even before Finland and Sweden decided to join the European Union and the launching of the Maastricht Treaty, which was built on the premise of the free movement of labour, goods, services and capital. Both countries joined the European Union in 1995. Their later commitment to European integration meant a commitment to the German-style ordo liberal state-imposed austerity policy in order to improve economic stability. This happened especially in Finland after the country, unlike Sweden, joined the European Monetary Union in 1999. However, the deregulation of global financial markets, the financial capital-driven economy and the impact of neoclassical mainstream economics meant a decline in the proportion of wages compared to productivity, rising unemployment and weakened social security. This also happened in Sweden.

It seems that Sweden and Finland forgot the lessons from the 1930s that letting unemployment rise despite the international economic recession may have disastrous consequences, as it did incrementally after the mid-1970s. This was partly because these two Nordic countries did not manage to generate enough investment in order to keep the unemployment rate low in the way they had done previously. It failed to act as a conduit to transform the advantages of the global economic infrastructure into a national Keynesian full employment regime, despite attempting to increase productive investment and attracting new foreign direct investments. Both countries experienced severe economic depressions in 1990s which still cast a shadow over political decision-making.

Lessons for the current crisis or the future?

The conditions under which post-Bretton Woods global capitalism exists, in Sweden and Finland as well as elsewhere, can be likened to the period of time leading up to 1930s, the period of the “self-regulating market”.That being so, ‘The Great Lockdown’, as the Financial Times coined the current crisis this week, can in some ways be compared to ‘The Great Depression’. It provides an array of policy challenges – and opportunities - for national and transnational economic and political elites in the following months and years. Should the recent warnings of Henry Kissinger (now 96 years old) that the current crisis may push us in the direction of fascism as it did in 1930s be taken seriously? In which case, a new type of Keynesian policy which provides a counterweight towards omnipotent global capitalism may be required to avoid skyrocketing unemployment and inward-looking xenophobic nationalism.

Further reading:

- Engelbert Stockhammer, Is the NAIRU theory a Monetarist, New Keynesian, Post Keynesian or a Marxist theory? Department of Economics Working Paper Series, 96. Inst. für Volkswirtschaftstheorie und -politik, (Vienna: WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, 2006).

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation. The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston MA: Beacon Press, 2001).

- Mark Blyth, Great Transformations.Economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Pauli Kettunen, 'The Transnational Construction of National Challenges. The ambiguous Nordic model of welfare and competitiveness', in Pauli Kettunen & Klaus Petersen, eds., Beyond Welfare State Models. Transnational Historical Perspectives on Social Policy. Series of Globalization and Welfare. (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2011) pp. 16–40.

- Pauli Kettunen, 'Wars, nation and the welfare state in Finland', in Herbert Obinger, Klaus Petersen & Peter Starke, eds., Warfare and Welfare. Military Conflict and Welfare State Development in Western Countries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) pp. 260–289.

- Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, eds., The Road from Mont Pèlerin. The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009).

- Sami Outinen, 'From Steering Capitalism to Seeking Market Acceptance: Social Democrats and Employment in Finland 1975–1998' Scandinavian Journal of History 42, 4 (2017) pp. 389?413.

- Sami Outinen, Nordic Social Democratic Reorientation, Employment, and Emerging Globalization 1975–1998 (manuscript, in progress).

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation. The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston MA: Beacon Press, 2001).

Links: