Sami language

A member of the Finno-Ugric language group and thus related to Finnish, Sami consists of three branches, sufficiently different from each other to be considered as separate languages.

Each of the three branches of Sami can be divided into two to four distinctive dialects. This diversity is a result of the scattered character of the Sami population, the lack of a central, hierarchical political organisation and, until recently, the lack of written forms.

Several of the Sami dialects have been, or still are, on the brink of extinction. This includes the dialects spoken in the Kola Peninsula, but also dialects such as Enare Sami (Finland) and South Sami (central peninsular Scandinavia). Since the 1970s, conscientious efforts have been made by Sami organisations, increasingly supported by government, to salvage and strengthen Sami language use. State supported media, including newspapers, textbooks and radio broadcasts, have boosted the Sami language. Lule Sami is one of the dialects that has recently experienced perceptible growth.

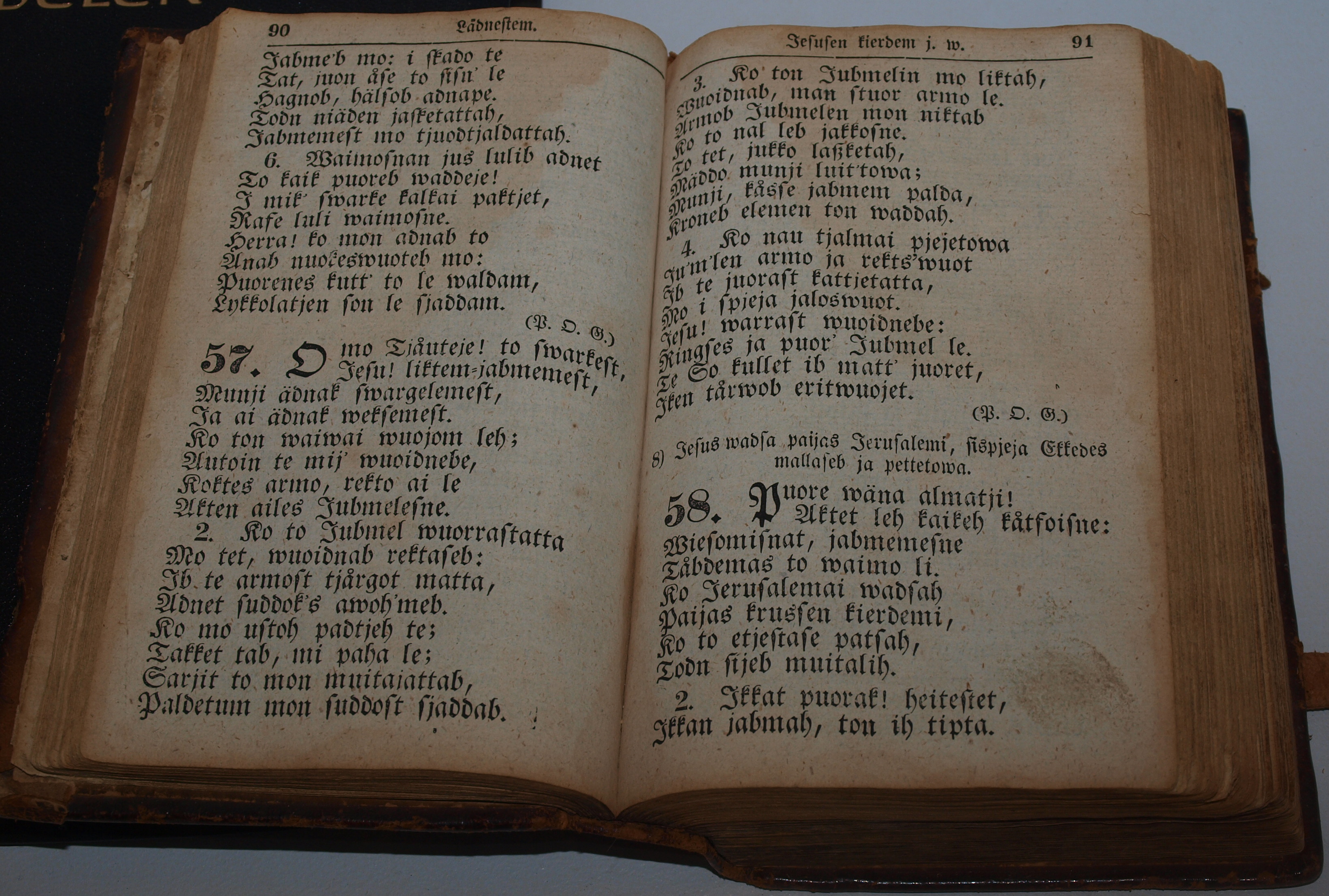

The vast majority of Sami speakers belong to the North Sami dialect, which is spoken and to some extent written by about 30,000 Sami, most of them in Norway. The main explanation for the resilience of this dialect from the State’s earlier assimilation campaigns is the relative isolation of the Finnmark interior. Though most of the reindeer-herding, semi-nomadic population of inner Finnmark had converted to Christianity by the mid-nineteenth century, not least because of the work of the puritan Protestant missionary Laestadius (1800–61), most of their cultural traditions and practices, including language, remained unchanged. Although the Bible was never translated into Sami, Laestadius and many of his pastors preached in Sami.

Traditionally lacking a script, standardisation of North Sami has been difficult and controversial. A Nordic Sami Language Council was set up in 1971, and it proposed a shared Nordic standard, which was eventually revised in 1979 and 1985. However, Sami had been written occasionally, using idiosyncratic spelling, since the 19th century. The first book written in Sami was Johan Turi’s Muittalus Samid birra (1910).

In spite of its indubitable minority status, the necessity of bilingualism in everyday life and the weak position of Sami languages outside of Norway, it is correct to conclude that Sami (especially North Sami, but to some extent Lule Sami as well) is thriving. In Finnmark and northern Troms, many public kindergartens and schools now use Sami (sometimes provoking protest from local ethnic Norwegians), and the Sami University College, which mainly uses Sami as its medium of instruction, was founded in Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino) in 1989. Many members of its staff publish academic texts in Sami. Language laws passed in 1991 (Finland; revised in 2004), 1992 (Norway) and 2000 (Sweden) are intended to protect and strengthen Sami language use.

Further reading:

Pekka Sammallahti, The Saami Languages; An Introduction (Karasjok: Davvi Girji OS, 1998).