Transnational interaction among feminist activists in the Nordic Countries, 1970s-2000

The Nordic countries are globally renowned as states that embrace gender equality. However, the region also has a rich history of feminist activism at the grassroots level. This history includes activism undertaken during ‘second wave’ feminism, from the late 1960s to the 1990s. During this period of time the women’s movements benefitted from interactions with non-Nordic political and cultural forces, and were influenced by resources and literature from outside the Nordic region.

The Nordic countries are globally viewed as ideal nations in terms of gender equality. The region is renowned for its exemplary track record regarding women’s political participation and representation, and it has positioned itself as a champion in gender-aware social provisions. Therefore, the welfare state and its benefits for women, such as parental leave and subsidised childcare, often take centre stage in our imaginations. What often goes unnoticed and undiscussed in relation to gender equality is that the region has a rich history of overtly feminist activism at the grassroots level. From the late 1960s into the early 1990s, during the time period referred to as ‘second wave’ feminism, several new women’s groups and organisations were established in the Nordic countries. Together, these groups and organisations formed the ‘new women’s movement’ (‘den nya kvinnorörelsen’ in Swedish, ‘den nye kvindebevægelsen’ in Danish, ‘uusi naisliike’ in Finnish).

Groups that belonged to the new women’s movements in the Nordic countries included, but were not limited to:

- Sweden: Grupp 8, Arbetets Kvinnro and Kvinnoligan.

- Denmark: Rødstrømpebevægelsen (or Redstockings Movement) and Kvindefronte.

- Iceland: Raudsokkahreyfingin.

- Norway: Nyfeministene, Kvindefronten and Brød og Roser.

- Finland: Marxist-Feministerna, Puna-akat/Rödkäringarna and Naisten kulttuuriyhdistys.

Groups like these were predominantly autonomous, meaning that they were not directly or officially part of political parties, trade unions, public institutions or other wider social movements. Individual groups and organisations were established and disbanded at different points in time, but the wave of feminist activism they created lasted into the mid-1990s.

Feminist activism in the Nordic countries varied over time and differed depending on whether it took place in the country, city or town. These variances led to feminists organising themselves in distinct ways in each of the five Nordic countries. For example, Swedish feminists targeted and worked with the state to a larger extent than their Danish counterparts. Unlike Swedish feminists, Danish activists kept their distance to official political institutions. In Finland, feminism as a distinct social movement materialised noticeably later than in the other Nordic countries. The Finnish movement also remained relatively small. In Iceland, consciousness raising groups, or groups where women gathered together to talk about their lives and feminist outlooks, were never a significant part of feminist activism.

There is no one social, political, cultural or historical model that perfectly explains feminist activism in the Nordic countries from the late 1960s to the 1990s. It is important to emphasise that differences between feminist activism within the Nordic region were partially due to activists in each Nordic country engaging with a wide range of varying international influences. From reading foreign feminist magazines to translating books into the Nordic languages as well as attending international meetings at home and abroad, Nordic feminists actively engaged with material from abroad.

Therefore, the feminist activism that took place during the second half of the 20th century did not develop in the Nordic region in isolation from the rest of the world. Outside influences and cross-cultural exchanges played a meaningful part in bringing feminist ideas and practices into the Nordic countries. Nordic feminists were influenced by events, initiatives and campaigns that took place in various locations, for example, from the United States to Great Britain, Italy and the Netherlands.

| Feminist pin-badges: Two badges from 1970s produced for women’s festivals in Copenhagen, Denmark courtesy of kvindehus.dk. One badge produced by Swedish Grupp 8 in the 1970s. Photo: Author. |  |

Examples of transnational feminist communication and co-operation

Literature:

The books and magazines produced by feminists within and outside the Nordic countries were an important source of inspiration for Nordic feminist activists who were members of the new women’s movement.

During the 1970s, feminist activists, many of whom belonged to openly socialist-minded groups such as the Swedish Grupp 8 and Arbetets Kvinnor or the Danish Redstockings, read the works of early 20th-century female Marxist thinkers such as Alexandra Kollontai, Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg. Nordic feminists also considered canonical socialist male thinkers and writers, such as Vladimir Lenin, Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, as significant. Their works were often cited in reading lists composed for feminist literature circles and consciousness raising groups.

Nordic feminist activists also read more contemporary feminist texts, written in the 1970s and 1980s. They read books by feminist thinkers such as Kate Millett, Juliett Mitchell, Sheila Rowbotham, Shulamith Firestone and Germaine Greer, either in their original language of publication (often English) or as translations into the Nordic languages. For example, Kate Millett’s foundational book Sexual Politics, originally published in English in 1970, was translated into Swedish, Norwegian and Danish the following year. The book was published in all three Scandinavian countries in 1971 by mainstream publishers (rather than feminist publishing houses).

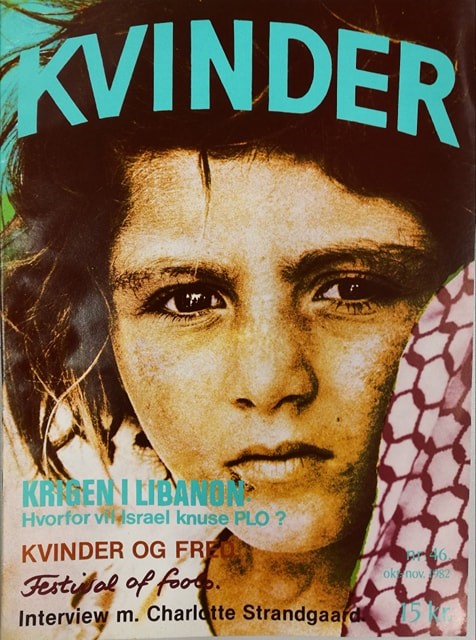

In addition to books, feminist activists across the Nordic region produced magazines and bulletins. These publications tended to include articles on various international topics. Magazines such as the Danish Kvinder, the Swedish Kvinnobulletinen and the Finnish Aikanainen-Kvinnotid exposed their readership to foreign influences by translating or paraphrasing articles that had been originally published in e.g the West-German feminist magazine Emma and the British publication British Spare Rib. The Nordic magazines also often cited each other. Nordic feminist activists covered several transnational topics in these magazines: they wrote travel diaries, exchanged travel tips and more generally showed solidarity to fellow feminists and women living in both the Global North and the Global South as well as communist Eastern Europe.

Cover of Danish feminist magazine Kvinder from 1982, courtesy of kvindehus.dk. Photo: Author.

Events and activities:

From the 1970s to the 1990s, feminist activists from across the Nordic countries gathered to take part in events that brought together an international array of participants. Some of these events were organised by Nordic feminist activists and took place within the Nordic countries. Nordic feminists also took part in international events held abroad. Examples of these events include, but are not limited to:

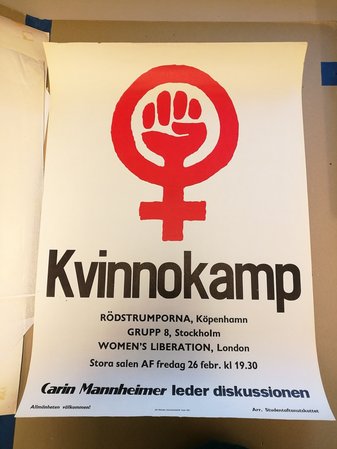

- 26th February 1971: Feminist activists belonging to the Swedish Grupp 8, Danish Redstockings and British Women’s Liberation Movement met in Lund, Sweden.

Poster from the 1971 meeting in Lund, which brought together feminists from Sweden, Denmark and the UK. Photo: Author.

- Summer 1971: Grupp 8 organised an international conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The conference was attended by feminists from Norway, the UK, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands.

- 24th of August 1974 and every summer into the early 1980s: Large feminist festivals were held in Fælledparken in Copenhagen, Denmark. The festivals were organised by the Danish Redstockings and later also Kvindefronten. The festivals attracted thousands of people – women, men and children from across the Nordic countries and further afield – creating space for transnational communication and cooperation.

Poster from Kvindefestival, held in Fælledparken, Copenhagen. In 1980 the festival had an international theme and had the motto ‘The struggle against women’s oppression is international’. Photo: Courtesy of Kvindeplakater and the Library in Kvindehuset, Copenhagen.

- Numerous women from the three Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway and Sweden) participated in the International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women, held in Brussels, Belgium from the 4th to the 8th of March, 1976. Icelandic feminists did not participate in person, but sent in a written statement. The Scandinavian participants provided testimonies on e.g. abortion legislation in Norway, the legalisation of pornography in Denmark in 1969 and its effect on women, and women’s experiences of sexual violence and rape in both Denmark and Norway.

- The mid-decade World Conference of the United Nations Decade for Women and the accompanying shadow conference were held in Copenhagen, Denmark from 14th to 30th July 1980. The official UN conference as well as the activism that formed at its fringes brought together a global array of feminist activists and women, many of whom were from across the Nordic countries. Feminist activists from the Nordic countries attended the conference in person and reported back to the other Nordic countries e.g. by writing articles for local or national feminist magazines and bulletins.

- Nordisk Forum, organised by the Nordic Council of Ministers, was attended by women from across the Nordic region in Oslo, Norway in 1988 and in Turku, Finland in 1994.

Moments of transnational interaction among feminists from the Nordic countries, as well as between Nordic activists and feminists further afield, often relied on personal connections, contacts and experiences abroad. Several women who took part in the new women’s movement in the Nordic countries had lived abroad or travelled extensively, therefore coming into contact with feminism abroad rather than at home. When returning to their countries of origin these women were in a position to bring back fresh ideas and practices with them. For example, many Nordic feminists attended feminist summer camps on the Danish island of Femø. These camps were held annually from 1971 onwards. They were initially organised by the Danish Redstockings. Femø summer camps brought together feminists from multiple countries, most significantly the Nordic region but also from other countries, e.g. West Germany and the United States.

Several concrete feminist practices used by feminist activists in the Nordic countries originated abroad. For example, Feminist Radical Therapy (FRT), a form of collective therapy popular in Finland during the 1980s, was imported to Finland from Berkeley, California via the Netherlands. Feminist self-defence had a similar trajectory: It was brought to Denmark by U.S. feminists and then made its way across the Nordic countries when feminist activists travelled and exchanged ideas and practices. Similarly, knowledge regarding menstrual extractions, the practice of inducing one’s period, was brought to Denmark from the United States. A member of the Danish Redstockings had first learned of menstrual extractions from U.S. feminists while living in California. She then imported the practice upon her return to Denmark.

Global politics:

Nordic feminist activists were affected by and involved in discussion on the global politics of the period which of course varied from late 1960s to 1990s and included, perhaps most importantly, the dynamics of the Cold War, decolonisation and anti-imperialism, the threat of nuclear warfare, and the international race between socialism and capitalist-liberalism.

Nordic feminist activists often voiced their solidarity towards women living in the Global South. Feminist magazines such as the Swedish Kvinnobulletinen, Danish Kvinder and Finnish Akkaväki – Naisten Ääni regularly published articles discussing the problems faced by women in various locations around the world, from Chile to Vietnam, and from South Africa to Palestine. Nordic feminists also took part in wider demonstrations against e.g. the Vietnam War and the Chilean coup d’état of 1973. Danish feminist publications arguably showed a greater interest in the indigenous rights of Greenlanders by writing about the new women’s movement in Greenland than the other Nordic feminist publications.

Nordic feminists also wrote about and commented on the rights of immigrant women and the conditions under which they lived in the Nordic countries. This topic was of significance, at least initially, in Sweden and Denmark, where the number of guest workers had increased significantly during the 1960s and 1970s. Many of the families of these guest workers had followed them through family reunification increasing the number of women from areas such as Eastern Europe and the Maghreb region, amongst others. Subjects included illiteracy and the importance of adequate language training.

Finally, the Nordic feminist peace movement (Kvinnor för fred, Kvinder for Fred, Naistet rauhan puolesta) was a truly transnational feminist project. It brought together women from across the Nordic region, and beyond. The movement campaigned for nuclear disarmament and pacifist approaches to global Cold War politics. The Nordic feminist peace movement organised three protest marches during the 1980s: in June 1981 from Copenhagen to Paris, in July 1982 from Stockholm to Minsk, and in August 1982 from Oslo to New York and onto Washington D.C. Nordic pacifist-feminists also took part and showed interest in peace camps abroad, such as Greenham Common in England and La Ragnatela in Comiso, Sicily.

Further Reading:

- Drude Dahlerup, Rødstrømperne – Den danske Rødstrømpebevægelses udvikling, nytænkning og gennemslag 1970-1985 (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1998).

- Drude von der Fehr, Anna G. Jónasdóttir and Bente Rosenbeck, eds., Is There a Nordic Feminism? Nordic Feminist Thought on Culture and Society, (London: UCL Press, 1998).

- Elisabeth Elgán, Att Ge Sig Själv Makt: Grupp 8 och 1970-talets feminism (Halmstad: Bulls Graphics, 2015).

- Minna Helminen, Väkevää Akkaväkeä – Naisten Kulttuuriyhdistys 20 vuotta (Helsinki: Valopaino, 2002).

- Solveig Bergman, ’Women In New Social Movements’, in Equal Democracies?: Gender and Politics in the Nordic Countries, eds. Christina Berqvist, Anette Borchort, Ann-Brote Christinsen, Viveca Ramstedt-Silén, Nina C. Raaum and Au?ur Styrkásdóttir (Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1999), pp. 97-117.

Links: